Projects

Projects

Projects

Projects

Projects

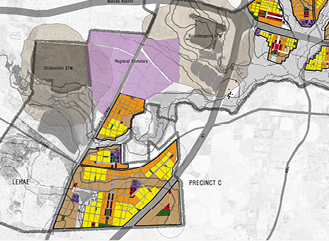

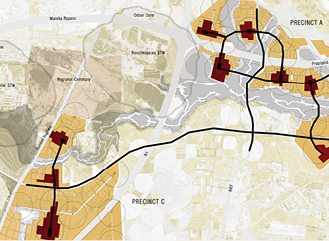

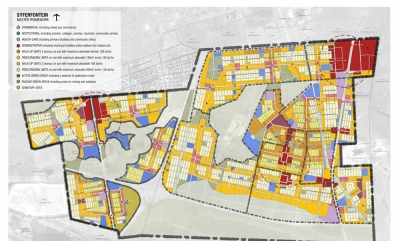

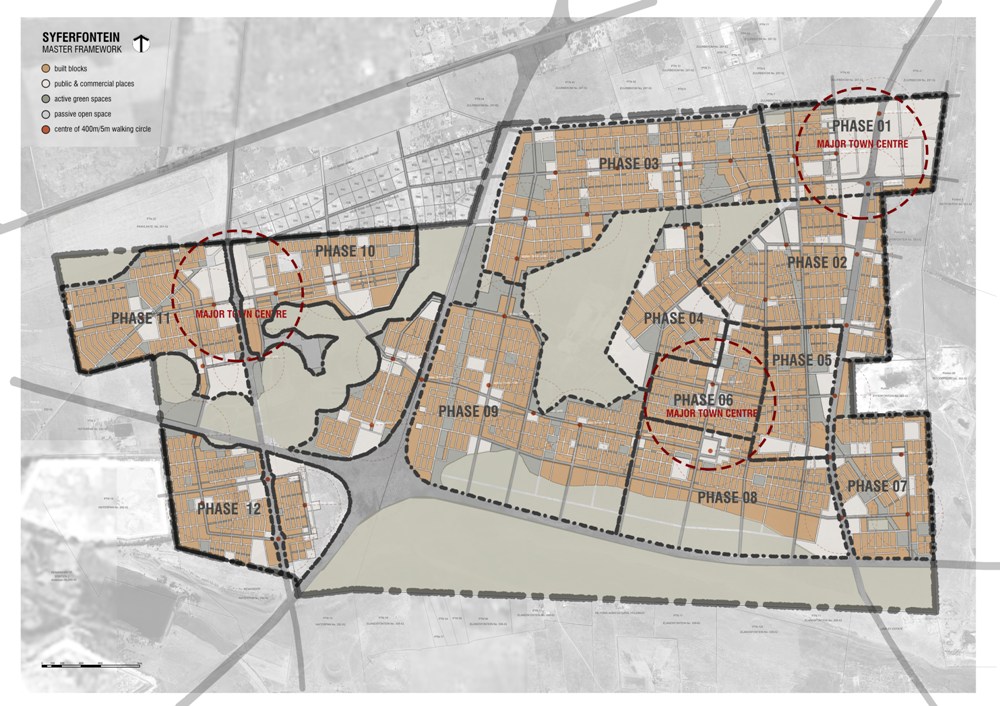

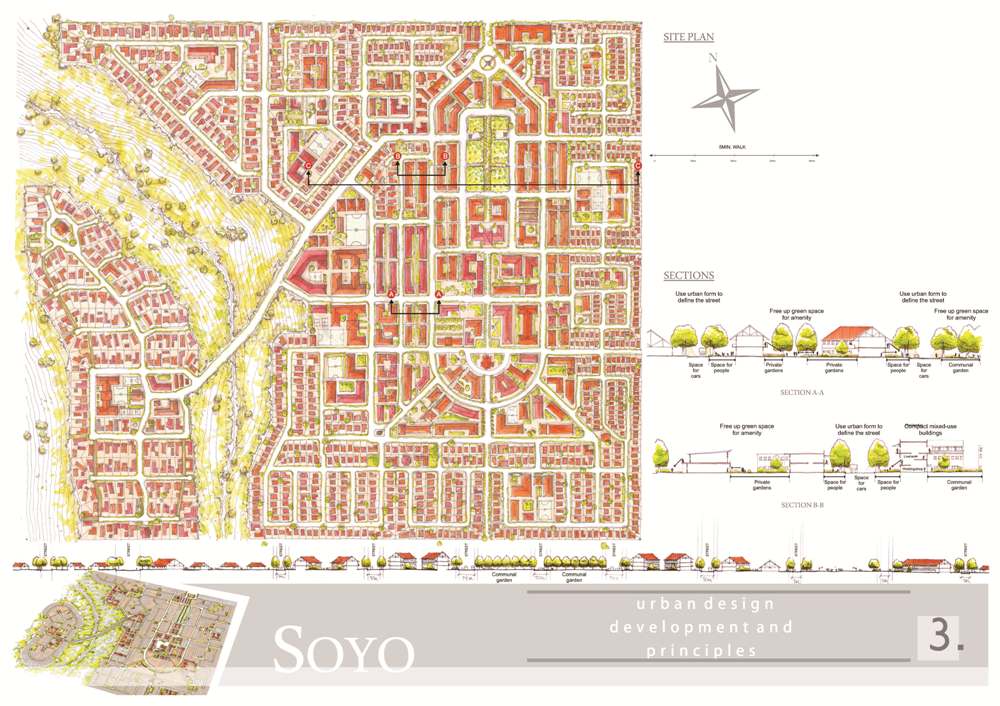

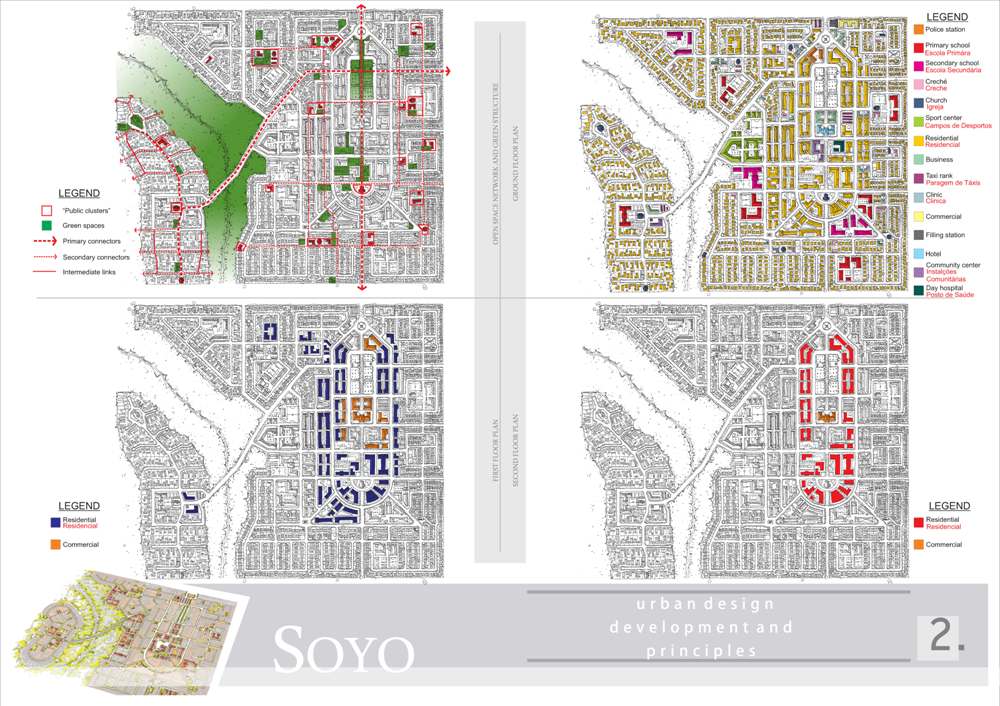

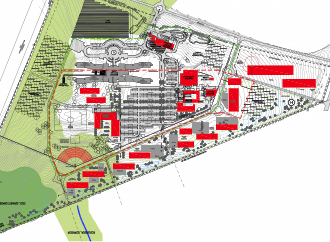

Newurban prepared an Urban Design Framework that included an Urban Development Plan, an Implementation Strategy and a Management Framework that included Urban Design guidelines and coding of the built form.

The development aims to create 14 315 new residential units. The New Smart City will include social amenities such as schools, churches and medical facilities supported by industrial zones and retail structures.

The Urban Design Framework had a particular focus on not just providing the client with a tool to guide development in the city, but also creating a vision of the city the town can become. The masterplan encompassed the development parcels within the city to ensure the development happens cohesively enriching the neighbouring development parcels as well as their own.

Development guidelines for the parcels serve to create a sense of space within the city and establish a narrative that runs throughout the whole city. The renders and fly-over video of the development provide the tools to envision the future city easily.

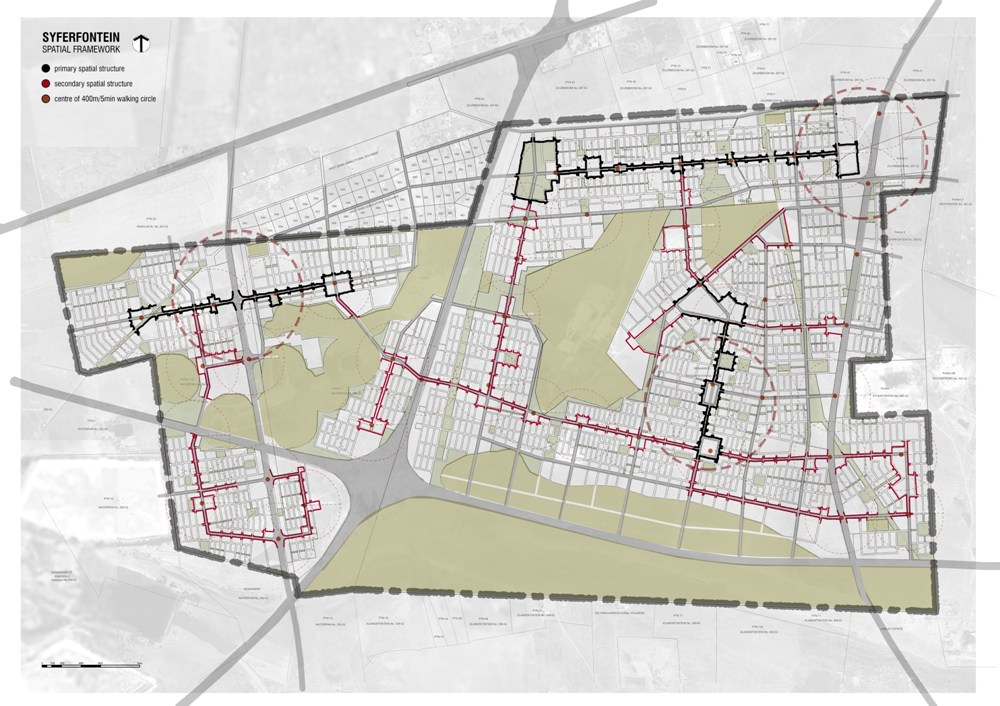

Newurban provided an Urban Design framework for the 170ha to guide the development of the residential estate as well as support the Township Application to the Council. The aim of the Shareholders (Stokvel) of the land was to develop the property for residential use and optimise the land value.

Newurban was mandated to negotiate with the neighbouring landowners on behalf of the client to ensure all parties could develop their land optimally without negatively impacting the other.

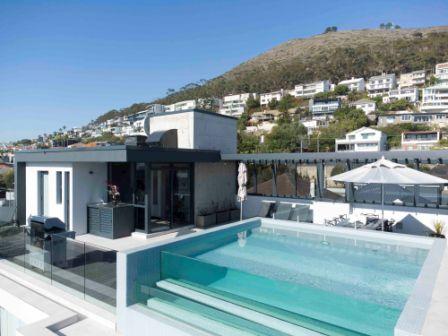

A multi-level luxury apartment rental to form part of the Shell Lodges Group.

This apartment building is located in Sea Point in Cape Town and consists of 3 multi-bedroom apartments. Each apartment takes up a floor of its own to maximise the view of the Atlantic Sea Board. All the apartments have access to the pool and entertainment area on the roof. Due to a limited site, it was decided to equip the building with a car lift as well as a passenger lift.

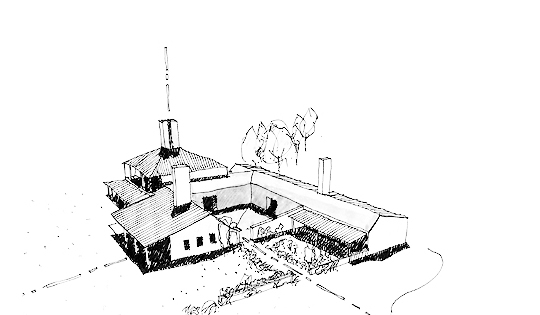

NewUrban were appointed to do a high-level Visual Impact Assessment (VIA) as a requirement for the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA). This VIA is done according to the Guideline for Involving Visual and Aesthetic Specialists in EIA Processes (Edition 1) as compiled by the Provincial Government the Western Cape Department of Environmental Affairs and Development Planning dated June 2004.

The project falls within in the George Municipality and the property under discussion is located opposite to the George Airport, on portion 4 of farm 208. The urban design vision prepared by NEWURBAN Architects & Urban Designers was done for the full Airport support zone. The VIA is site specific and is compiled taking into consideration a Category 4 development which entails a possible high visual impact according to the Guideline for Involving Visual and Aesthetic Specialists in EIA Processes.

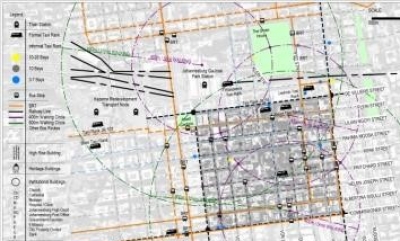

The Inner-City Cross Border Shopping Precinct Implementation Plan is a desktop study to serve as a decision-making tool to an Implementation toolkit to motivate the revival of the Inner City from an economic and strategic intervention strategy. The purpose of the report was to provide the economic strategies and interventions in creating a conducive Cross-Border Shopping Precinct within the CoJ Inner City.

The implementation plan should aim to leverage regional / area comparative and competitive advantages to develop and catalyse local economic development and to further create employment and entrepreneurship opportunities. The implementation plan will provide operational support for mixed land use that encompass a wide range of spatial planning instruments that will aim to advance the urban regeneration of the area.

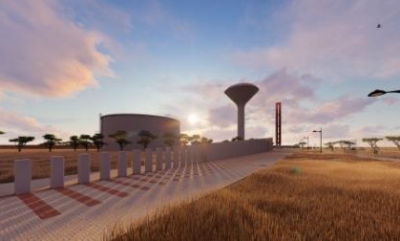

The tower was commissioned with a water tower in Etwatwa to celebrate Nelson Mandela’s life and simultaneously become a beacon in the landscape for the people of Etwatwa. The obelisk shaped tower stretches 30m into the air and acts as an enormous sundial to indicate the day of Mandela’s birth and death. Accompanying the Obelisk is 95 separate concrete columns that escalate in height to indicate Mandela’s entire life cycle (95 years) but also showcasing some of his life-altering events and contributions to our freedom and democracy in South Africa.

The Obelisk is monumental in nature, simplified by design and is finished in an oxide red colour to symbolize the soil in the area.

This concept is carried through the different design elements and is achieved by the following strategies:

- simplicity of the structure

- robustness of materials

- colour use

- and material use.

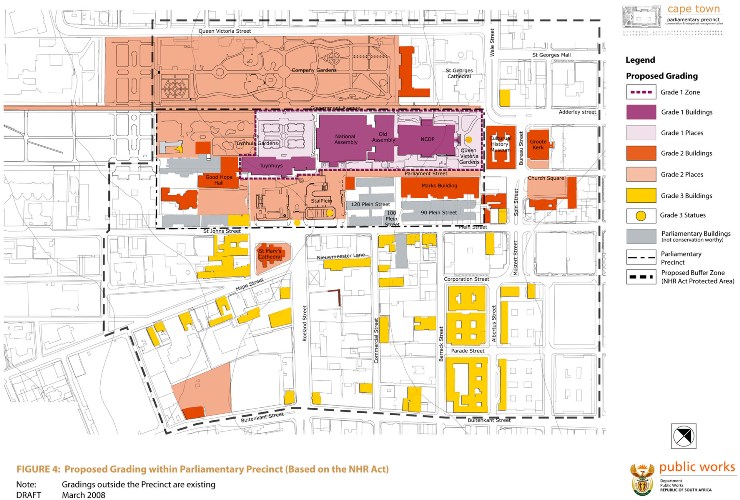

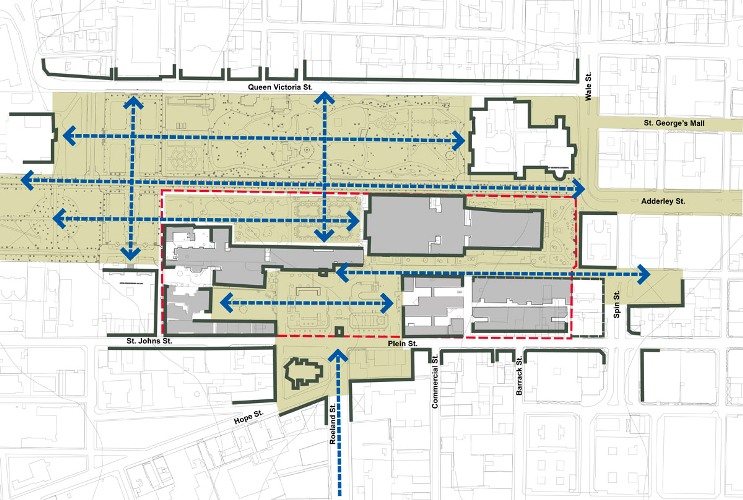

The project aimed to design management and implementation guidelines for the Salvokop Precinct in order for the Department of Public Works to successfully package and integrate Public Private Partnership (PPP) projects and to be able to determine whether a project has successfully met its objectives and desired outcomes. Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) also needed to be developed against which the performance of the project can be determined during and after implementation as well as for the rest of the duration of the project’s life (post-PPP).

The project for the general upgrading of the existing Tembisa campus hall. In addition, the client required a design proposal for upgrading and modernizing the entrance to the college Hall.

The design approach in revamping the hall is to update the existing Department of Works utilitarian aesthetics of concrete frame, face brick infill and steel louvres to a contemporary style that combine modern materials and natural finishes and perforated screen elements.

Also addressed in the design to improve the current low level of natural light that penetrates the main hall by removing the existing very dense sun louvres and to replace them with redesigned sun shading that are angled in a way that windows are protected from aggressive western sun but that Southern reflected light can penetrate without obstruction.

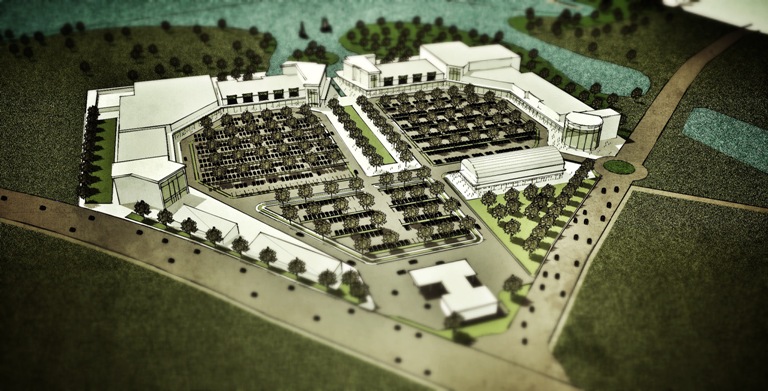

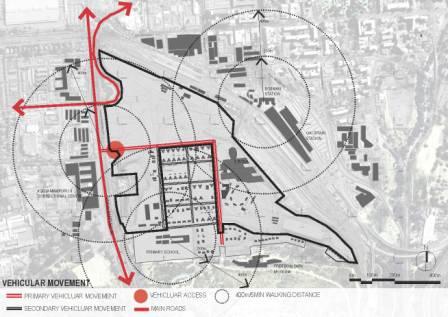

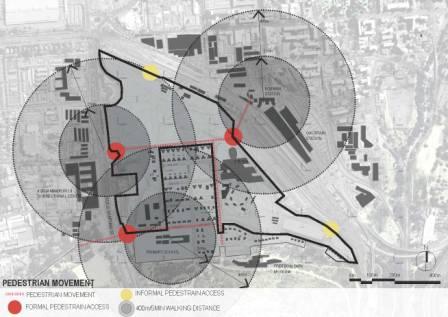

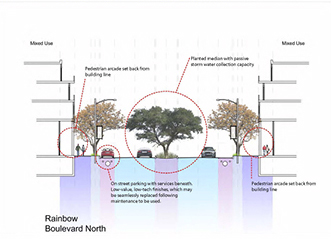

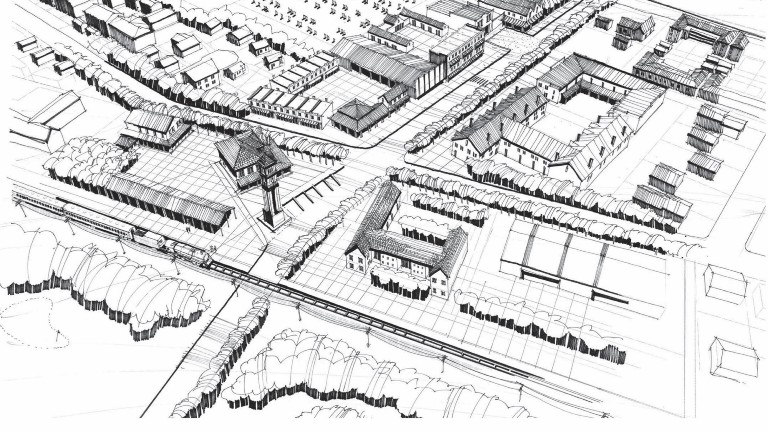

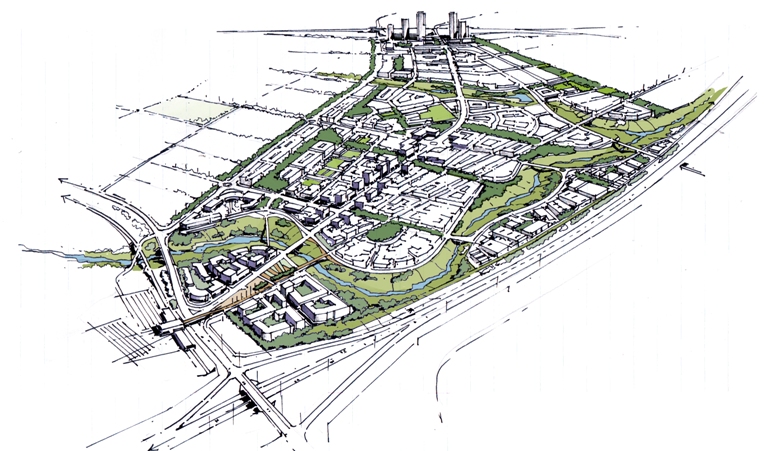

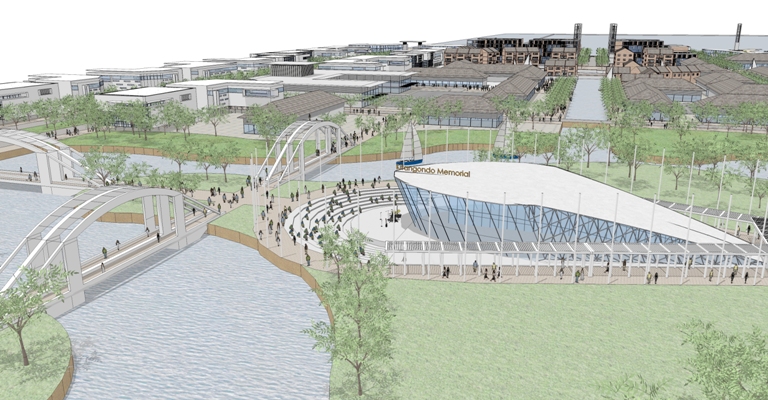

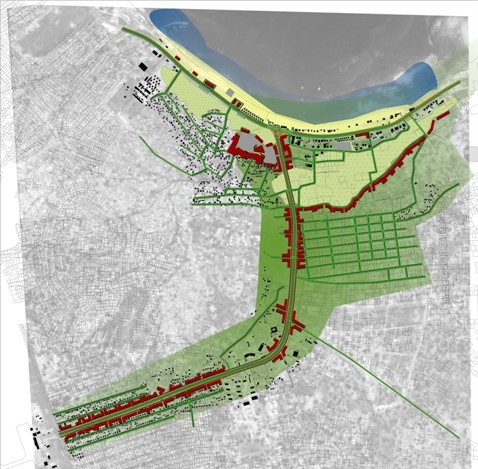

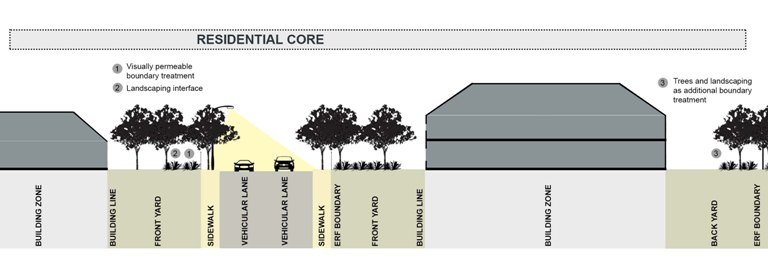

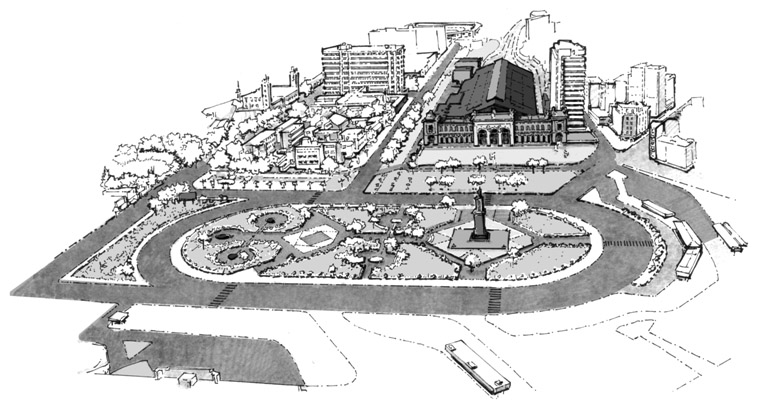

The Rainbow Junction Development is situated in the centre of the new zone of choice of the City of Tshwane, 6km to the north of Church Square. It is strategically positioned at the northern gateway to the Pretoria CBD, with proximity to and within easy reach of the CBD and Wonderboom Airport. Bordered to the east by the Apies River, which runs the full 4 km length of this development node.

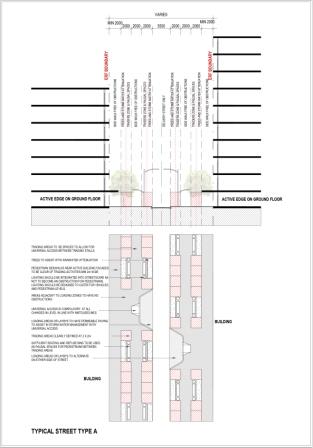

This development will be one of the major northern gateways to Tshwane. Vistas towards the Apies will be ensured by means of the landscape and urban design guidelines. Apart from vehicular movement, the streets will be designed as special streets with integrated landscaping and urban design qualities. This is especially the case with street intersections.

The placement of iconic buildings on strategic sites within the development will be prescribed by the Urban Design Guidelines. This will not only provide landmarks for orientation within the development, but also act as the visual manifestation of the start of a new urban core for the whole area. It is proposed that these iconic buildings have a distinct African character to enhance the unique identity of this development.

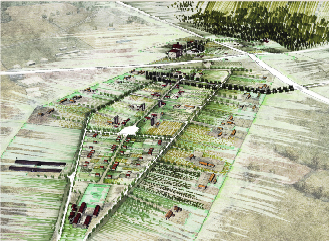

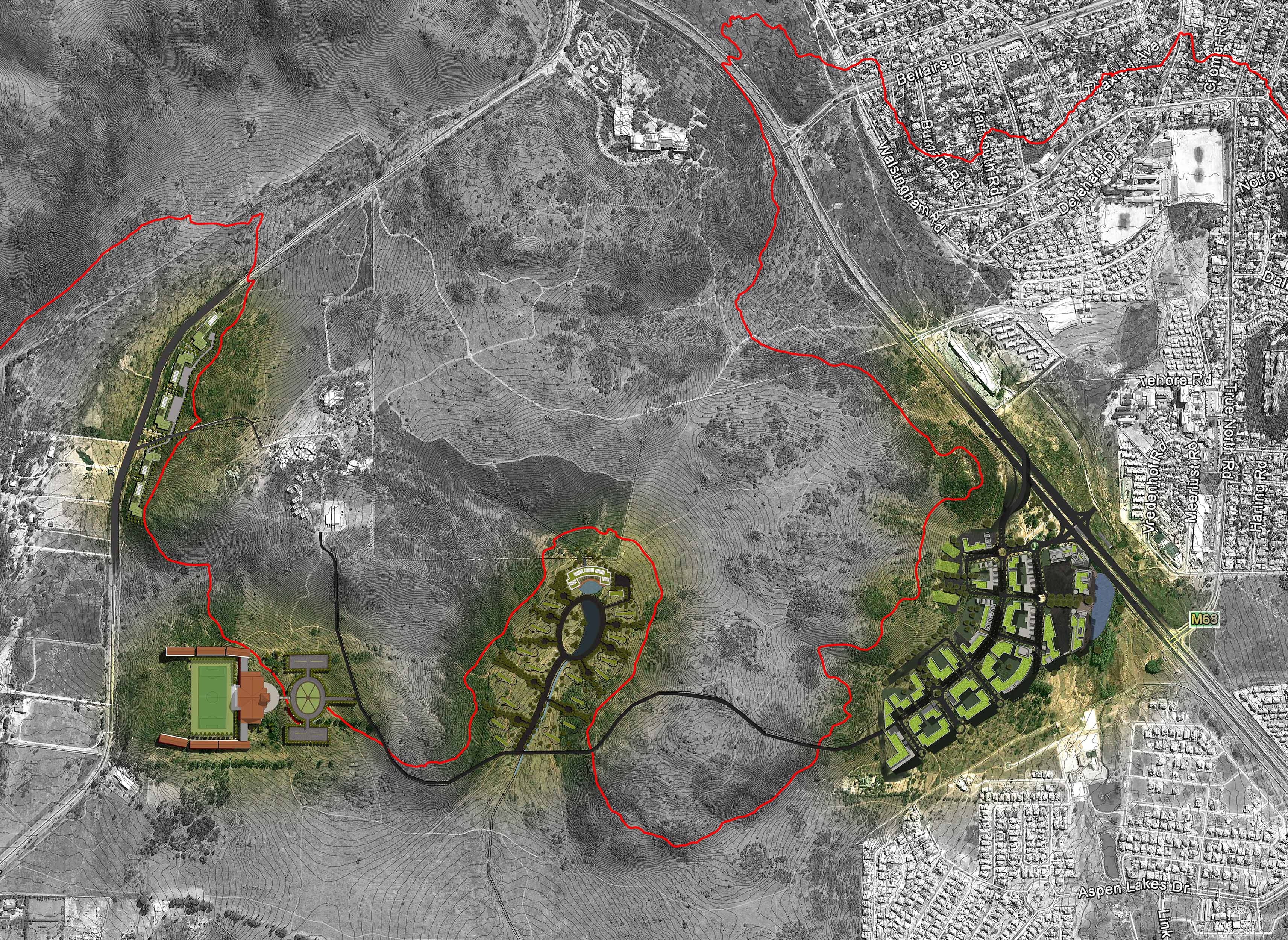

Southern Farms is a large-scale, mixed-use development proposal envisioned by a development company working in Gauteng, South Africa. The site allocated for the project includes large developable areas, protected wetlands and streams, existing farm land and a challenging topography.

The goal was to create an Urban Design Vision which would satisfy both the needs of future inhabitants and the developers while protecting and furthermore integrating the management of sensitive natural areas. The site is located on a piece of land that holds the potential to integrate the previously segregated Soweto into the rest of the Johannesburg metropolis, thus adding a politically driven layer to the decision-making process.

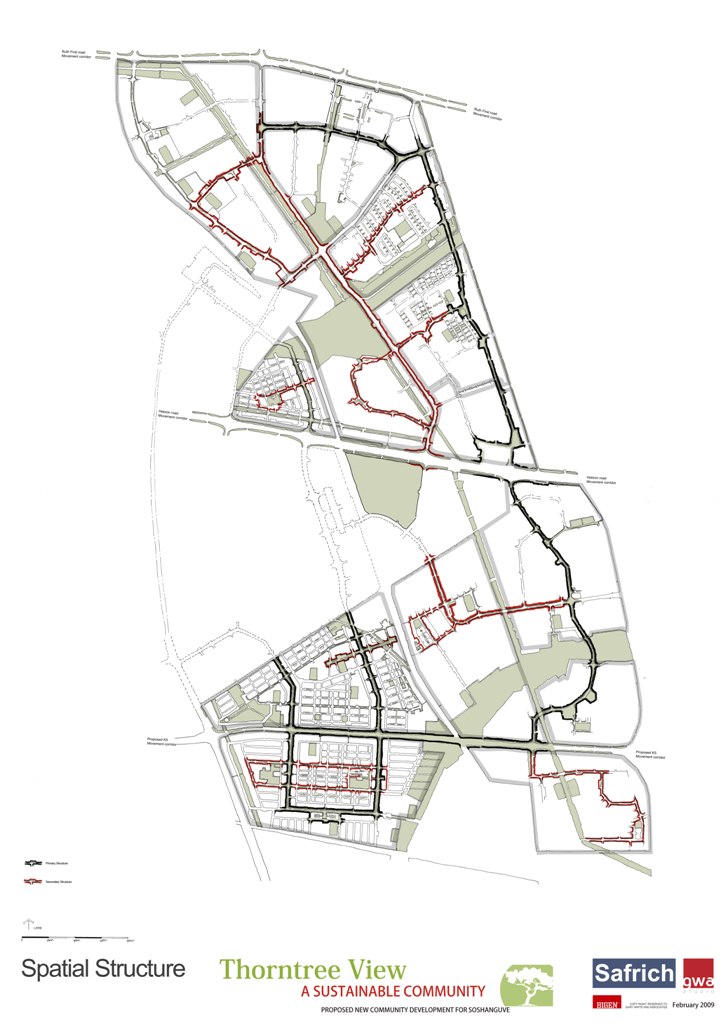

Posed with these constrains - protected natural areas, large vehicular routes posing disconnection of villages and a low budget, the key design concepts focus on finding solutions in a practical manner whilst creating places for people at the same time. After forming a strong concept to satisfy these initial needs, the biggest challenge was to devise a layout that could incorporate high densities of housing and a large number of dwellings. This was addressed with a responsive and sensible spatial structure while utilizing economic and linear geometries and the incorporation of adequate and accessible civic landmarks.

A land use cycle has been devised with input from all professionals, which aims at including undeveloped land in phases to support developing land. These will include agriculture, solar farms and natural area protection. The project is currently in the initial phases of development, with several years of site work envisioned before completion.

CNU Charter Award Winner - Region, City and Town 2016

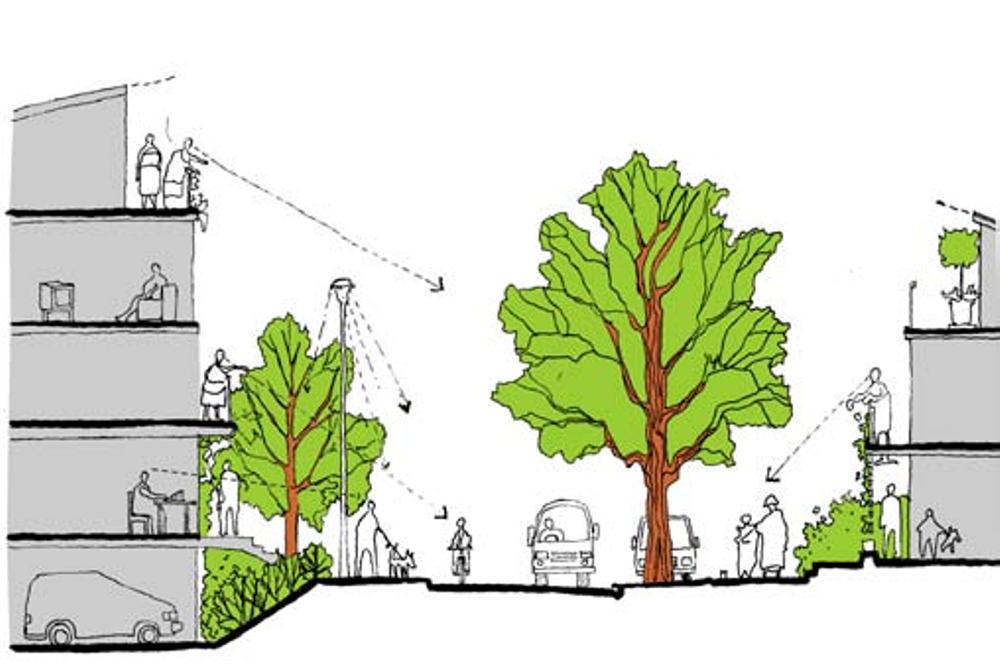

Building for Change/ Urban change. Urban and social sustainability are of great concern because they have been virtually ignored in current programmes and designs to re-imagine housing for the City of Cape Town. For urban development and housing could become the catalysts for an end to poverty, exploitation, segregation, inadequate housing, congestions, ugliness and homelessness within the city.

Resilience/ Resilient place making and buildings insure flexible urban spaces over time and is at the core of the housing infill concept. Spaces could transform in terms of accommodating a mix of uses. Time in enabling buildings and places to be adapted, personalise and changed in use over time according to the needs of occupants. All of the above elements are important for long-term sustainable urban environments and housing.

Smart living/ The biggest challenge is to take an ideal, like sustainable development, and make it into daily reality for all occupants of new houses and urban environments. Practical steps to help save money, improve safety at home, fight poverty, fight climate change, improve air quality and to protect the environment are in the hands of smart communities like Scottsdene.

Urban design principles/ Urban design adds social and environmental value by creating well connected, inclusive and accessible new places. Key principles include urban place making, street definition and articulation, visual access and choice, productive green public spaces, public participation and choice, quality of mixed income housing.

Entry into Deutsche Bank Urbanage Awards 2012

Pesented at TEDx CT2012

Covering a small portion of the historic campus of the former Government Garage site, the new intervention takes up the corner of two prominent streets, Kgosi Mampuru and Visagie Streets in the Pretoria inner city. Kgosi Mampuru Street, previously Bosman Street, was cleared of vegetation along this strip as a security measure during the apartheid regime, rendering a hard western urban edge. Most of the industrial buildings on the site were built between 1923 to 1945, heralding ubiquitous Kirkness face bricks. The buildings affected by the intervention, currently mostly standing vacant, will be incorporated into the larger Government Printing Works which is already located and operating in proximity on the same site. An existing, much contested fence, runs along the street edge – a National Key Point requirement.

The language of the proposed additions grows out of the idea of inserting new facilities within the eroded shell of the former brick warehouse. In order to re-use the structures for the print works, a minimum head clearance had to be achieved, resulting in the literal raising of the existing roof. The new building slips past the old in a series of planar elements of glass, rheinzink and steel. These planes then become a language of the new beneath the single unifying roof profile.

The new addition will preserve significant historic materials as far as possible – compatible but differentiated from the historic building. To preserve the historic character, the new addition will be visually distinguishable from the historic building.

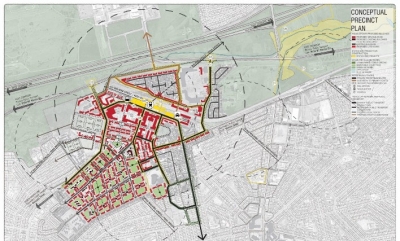

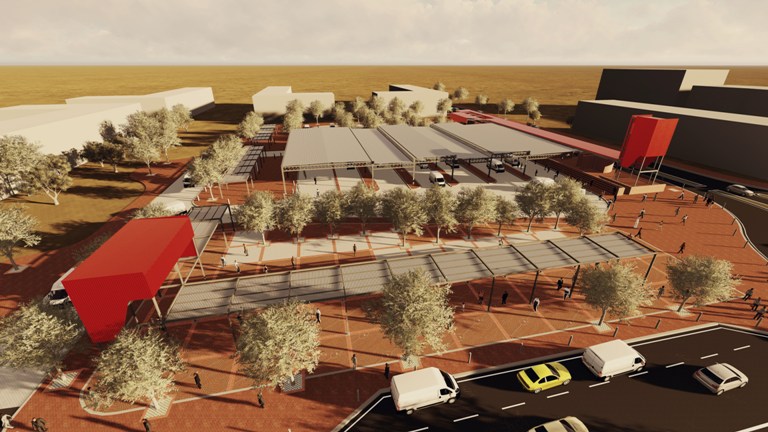

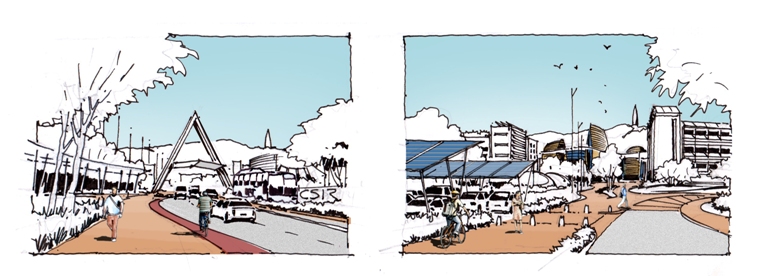

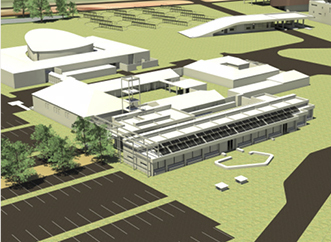

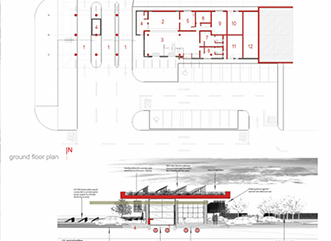

The approach to the design of this facility is to ensure that it will act as an intermodal public facility and not just a taxi or bus rank. The integration with the Mabopane Station is of utmost importance. Pedestrian flow and traffic flow guided the geometry of the site layout and the placement of the structures.

The project is designed for people who rely on public transport for their daily life, therefore pedestrian safety, comfort and dignity formed the basis of the design. Public facilities, like toilets, were placed on the most accessible positions and for the hawker facilities the most economically feasible positions were selected.

The layout of the facilities specifically the roof structure is done as a modular design that can be expanded or adapted as needed over time, with minimum interruptions.

The materiality of the building was determined by and generated from the programme of the project: steel construction is the most appropriate locally available building material in terms of the project’s specific function. Steel construction is also used extensively to shorten the construction time and to be able to get the facility operational as soon as possible.

The main notions informing aesthetic decision making includes legibility and a distinctive architectural identity. Legibility is very important in any public structure in order to ensure that users understand the structure and know instinctively where to find which facility. This concept is carried through the different design elements and is achieved by the following strategies:

- simplicity of the structure

- various scales are used for various functions

- colour use

- and material use.

- A distinctive architectural identity is central on an urban level in order to create awareness of the facility as well as to ensure that the complex becomes a landmark in the area.

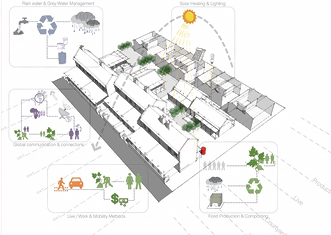

This sustainable development 5km for Cape Town CBD follows the perimeter-block design principal, placing the bulk of the building on the periphery creating more private courtyards for paring and recreating. The Maitland Housing development also focused on implementing passive and active energy solutions to improve the overall sustainability of the project and optimising the comfort of the end users though basic good design. A small scale commercial space was also included in the design due to the active spine that Voortrekker Road created.

The development responds to its environment by acknowledging the heritage building adjacent through design as well as the more modern building down the road. Accessibility and Legibility of the urban environment facilitates ease of use Ease of use are facilitated though legibility of the urban environment as well as the focus on alternative movement.

The Clayville Mega Housing Project is an integrated housing development within the Ekurhuleni Metropolitan Municipality, with a close proximity to the N1 and R21 Freeway. The Clayville Mega Housing Project acts as an infill development between Midrand, Tembisa, Olifantsfontein and the rest of the N1 Development Corridor.

Construction is currently ongoing and will provide various social amenities incl. schools, parks, a library, community centre, places of worship shopping centre and business stands. The area will benefit by the development through urban renewal, infrastructure upgrades and jobs.

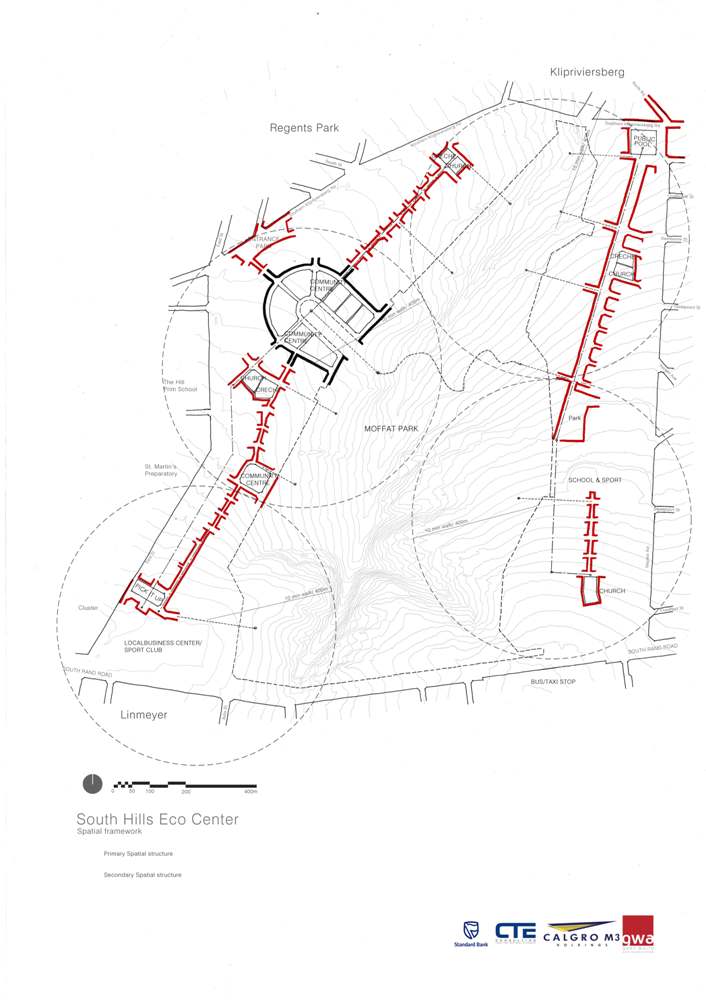

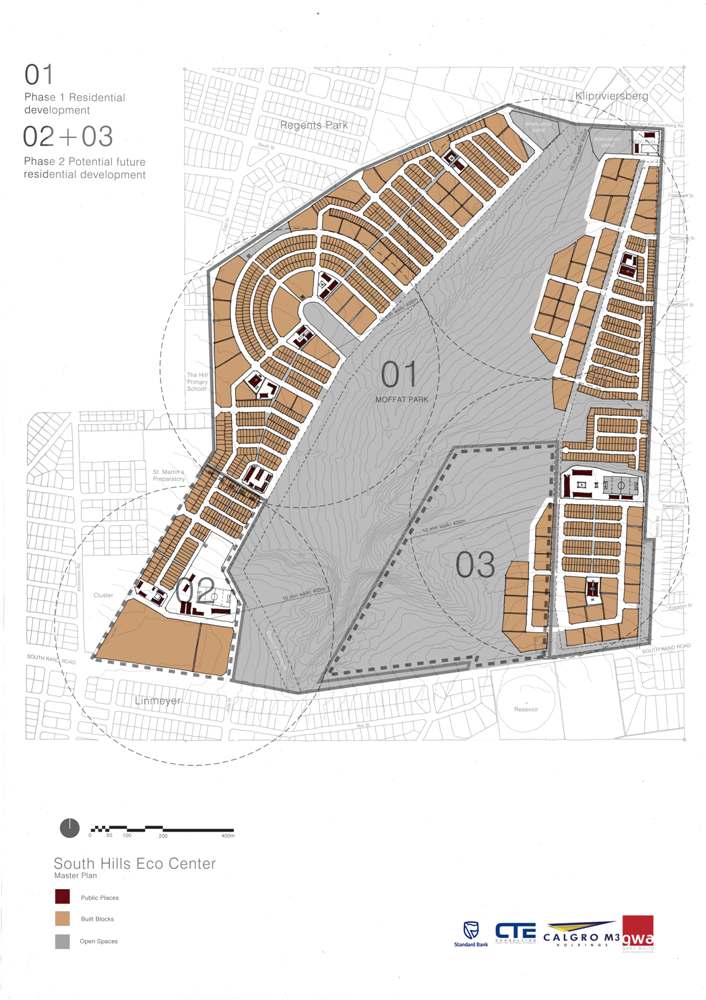

The South Hills projects is one of the premier integrated housing development for the City of Joburg with a mixture of housing tipes raging from fully subsidized housing to open market bonded housing. This housing development 5 km for Johannesburg CBD will provide homes to approximately 32 000 people.

This development uplifts the surrounding communities as well as it includes the upgrade of bulk and link infrastructure. Is also creates employment opportunities as local contractors and labour as well as local suppliers. the upgrading of existing community facilities form part of the project as well as skills and development programs.

A focus was place on creating a sustainable development with the inclusion of energy saving technologies for water, and electricity needs. Community facilities that form part of the development include parks, schools and religious buildings.

The City of Johannesburg is using this project as a cataylist for further infrastructure development with a focus on roads. widening, road water infrastructure and intersections to prepare the area for future residential developments.

The aim of the project is to establish a mixed use development, with a mixed use income and density spectrum. The site has easy access to main infrastructure roots as it spans between, the N1 and N12 freeways. This will be a Sustainable Human Settlement with a range of community facilities, Retail commercial and industrial activity.

The Spatial Development Framework provided the basic spatial structure, movement networks and the land use. The design improved access to basic services, and the development improved the Gap-market Housing Property Market.

n the African context trees play an important role, as they not only provide shade but also function as landmarks for orientation and as public buildings that become substitutes for covered outdoor spaces as part of the urban fabric. Large trees become the focus of public gathering places. Sizes of public squares formed around the trees are defined by the spread of the crown of the tree.

In the framework the tree has been used as the main structuring principle. Activity nodes are formed around existing trees and these meeting places organize the village. Public buildings and amenities are located around these activity nodes, strengthening the character and outdoor spaces.

An interconnected movement framework connects all these public nodes forming a system of pedestrian movement and meeting places.

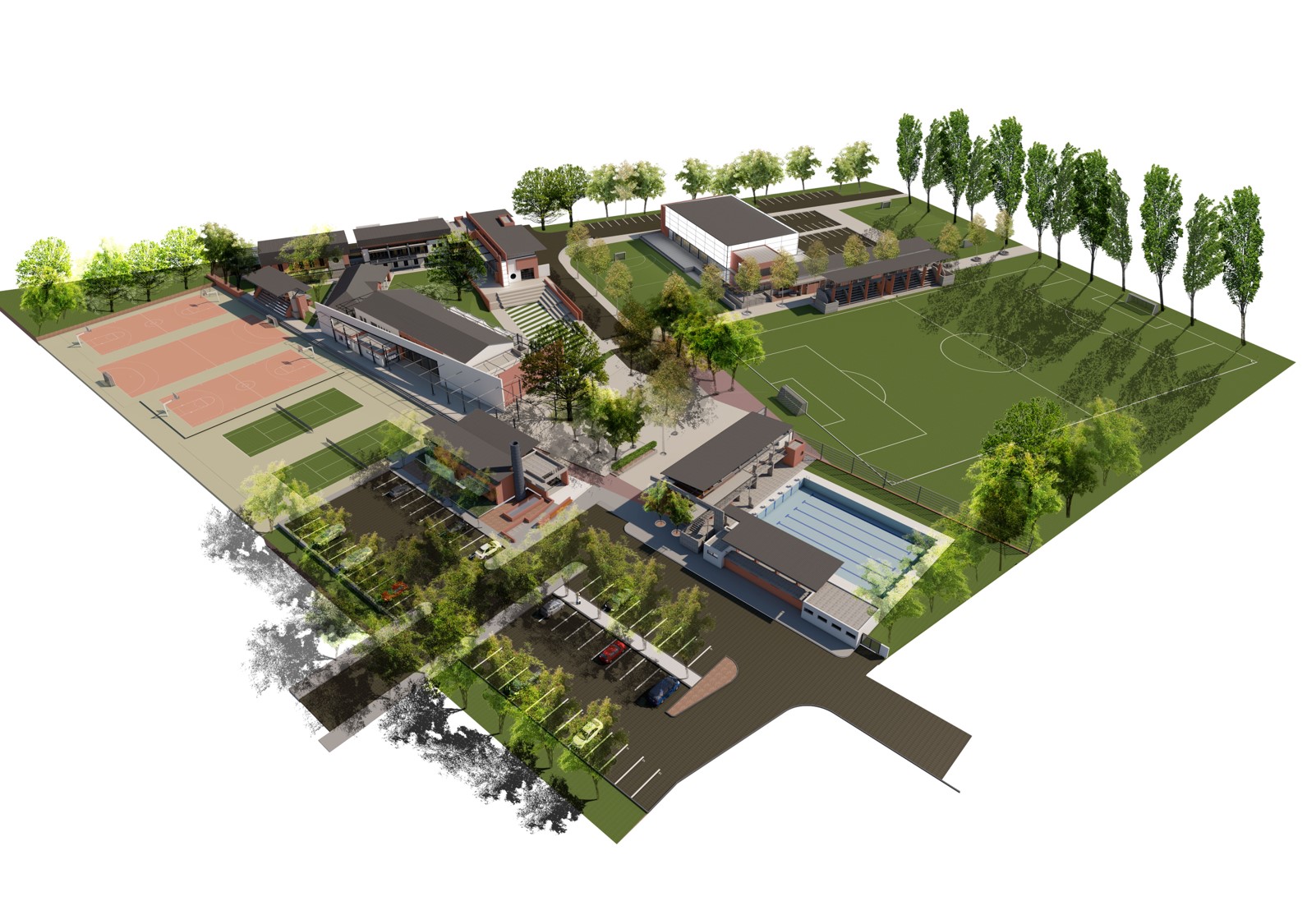

Paterson Park is an established open space resource situated between the suburbs of Norwood, Orange Grove and Orchards, in northern Johannesburg. Paterson Park itself is a relatively well maintained public open space, although as a public facility it is not as well utilized as its location and scale may suggest.

Facilities within the precinct include a children’s playground area, a Bowling Club, a multi-purpose Recreation Centre with tennis courts, and a War Memorial. The main focus of the development for Holm Jordaan Meago encompasses the development of the Recreational Precinct/ Block upgrade and development. This includes:

Upgrading the existing Recreational Hall and Tennis Courts and the construction of several new facilities including; a Multifunctional Sports Hall with adjoining spectator seating for the soccer field, a new swimming club, a Library and Craft Centre, and administration facilities. The scope will also include upgrades to the perimeter walls and all external works including parking facilities.

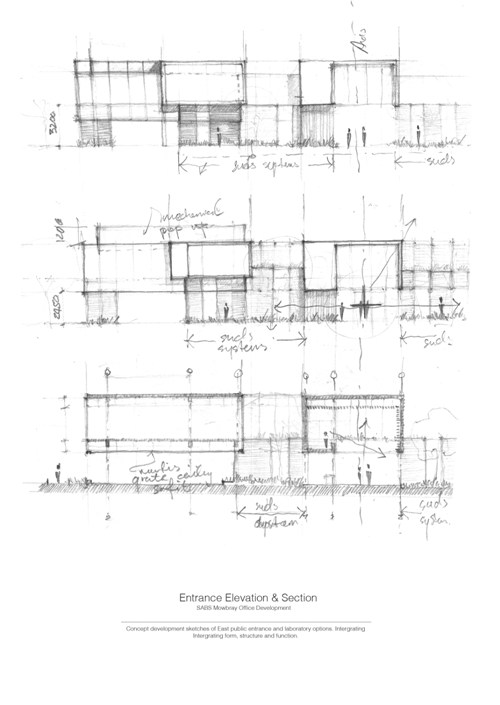

The existing offices and laboratories of the SABS did not comply anymore with modern standards and requirements, and had to be demolished to make way for new offices and laboratories. The new building would have to be built in a phased approach, to allow lab operations to continue. The new building would utilise the latest technologies and materials, such as polycarbonate cladding, low-e glazing and green technologies for energy saving purposes. The intention is for the building to be an example of the application of SABS standards, and would have laboratories complying with the highest international standards. The project was later cancelled by the client due to budgetary constraints.

This was for the refurbishment of the Stellenbosch offices of the CSIR. The work entailed the cladding of the external façade in Rheinzink for durability and low maintenance, the complete refurbishment of the reception foyer, seminar room kitchen and tea room, and 6 toilets. In the reception area meeting pods were introduced to enable staff to have meetings with visitors. The design is contemporary and in line with the CSIR corporate design manual, also prepared by Holm Jordaan Meago Architects.

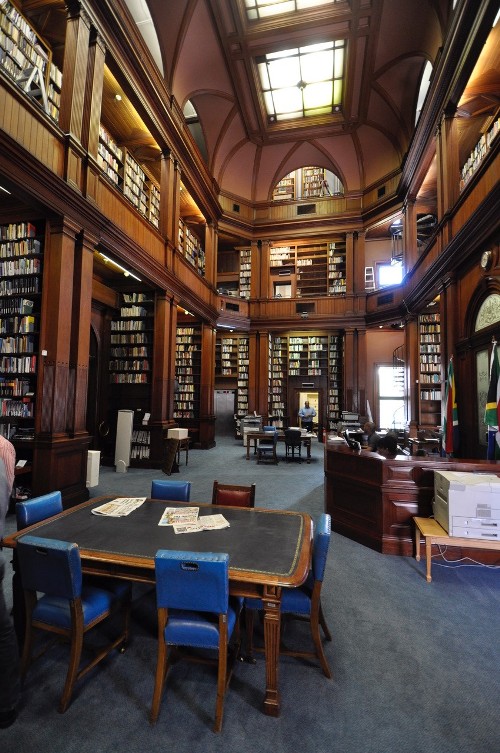

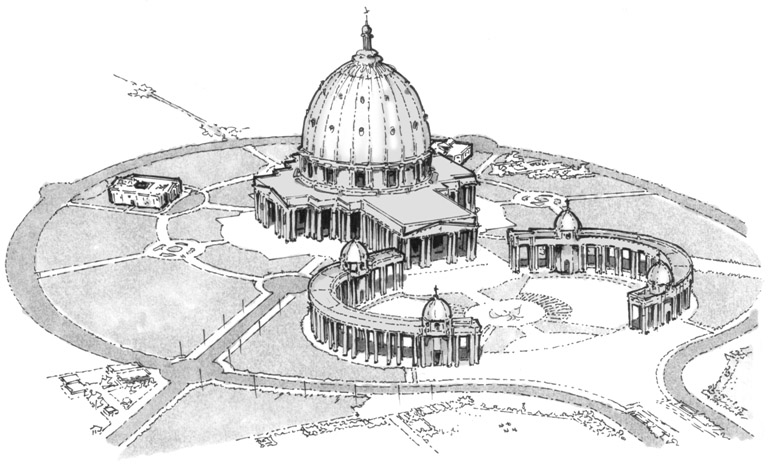

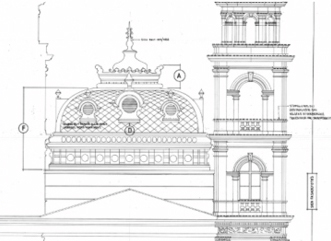

The project entails a comprehensive refurbishment and repair of the NCOP building, including HVAC, electrical & electronic installations. The National Council of Provinces site (NCOP) exhibits a virtue which is seldom found among historical places in South Africa, it is reflected in the inherent connectivity between the site and the history of the country. This connectivity is a relationship which spans from the arrival of van Riebeeck to present day democracy. More importantly, the story of the site is an ongoing narrative, as it continues to play a significant role in the journey of the rainbow nation and thereby contribute to the story of South Africa.

The NCOP building was completed in 1884 on a site originally forming part of the Company Gardens, and was close to the Colonial Office Building, which was later demolished to make space for the Cape Parliamentary Building.

The NCOP building is based on a prize-winning design by the architect Charles Freeman produced in 1874 in a competition for a new building to house the Cape Parliament. Freeman was dismissed as architect from the project after wrangling over cost escalations, when it became apparent that deeper foundations than expected would be needed. A reduced version of the original design was finally completed under HS Greaves and assisted by George Ransome in 1884. The most notable differences from the original design were the loss of colonnaded corner pavilions, a large crowning dome and secondary domes originally intended to flank the main entrance portico. It would therefore, appear that a substantial amount of Freeman’s original design did survive in the form of Greaves’ subsequent proposals.

The NCOP Building is of great historical significance in terms of its social/political and architectural importance. It is of great social significance with regard to its rare historical and archival collections, and of great architectural significance as a fine substantially surviving example of its period. The building has great local landmark significance and is of some technological importance relating to its very early in-house electric lighting system, which was probably the first of its kind in the city and one of the first in the country.

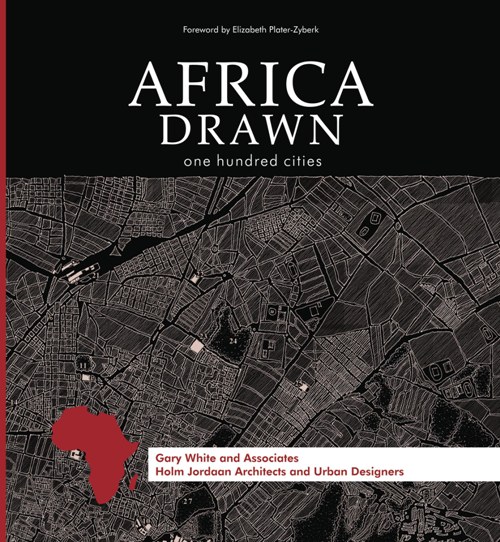

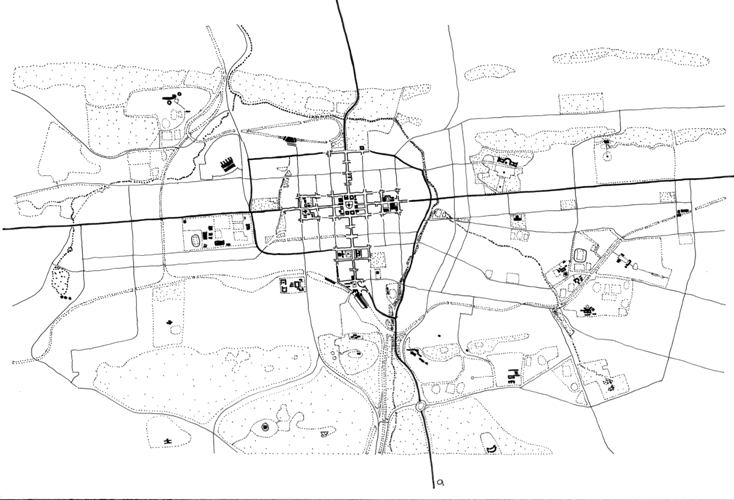

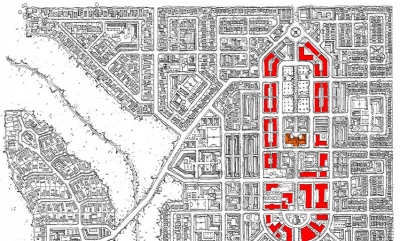

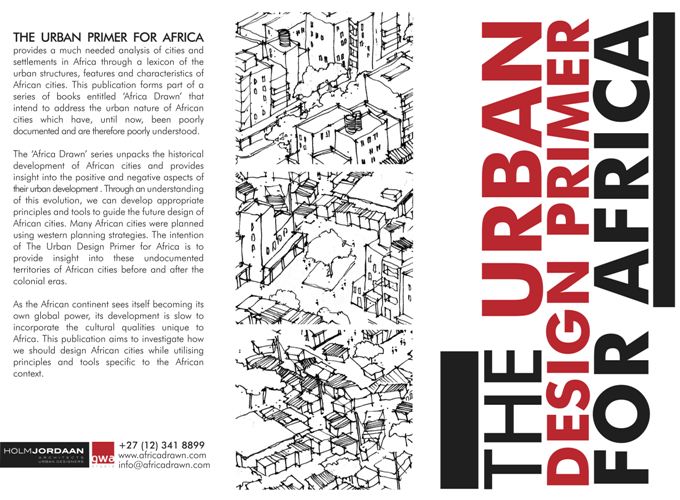

The Urban Primer for Africa provides a much needed analysis of cities and settlements in Africa through a lexicon of the urban structures, features and characteristics of African cities. This publication forms part of a series of books entitled ‘Africa Drawn’ that intend to address the urban nature of African cities which have, until now, been poorly documented and are therefore poorly understood.

The ‘Africa Drawn’ series unpacks the historical development of African cities and provides insight into the positive and negative aspects of their urban development. Through an understanding of this evolution, we can develop appropriate principals and tools to guide the future design of African cities. Many African cities were planned using western planning strategies. The intention of The Urban Design Primer for Africa is to provide insight into these undocumented territories of African cities before and after the colonial eras.

As the African continent sees itself becoming its own global power, its development is slow to incorporate the cultural qualities unique to Africa. This publication aims to investigate how we should design African cities while utilising principles and tools specific to the African context.

In its latest zoning scheme, the City of Cape Town relaxed the requirements for second dwellings, making it a default use right instead of a consent use right, in order to encourage densification of suburbs. This project is for a small second dwelling on a Durbanville property. The design uses a few simple materials and a minimalist approach to create an elegant contemporary house that has a positive dialogue with the street. Face brick screens are extensively used to provide privacy and solar control.

The project entails the sub-division of a large erf in Riebeek Kasteel, and the development of 4 new dwellings. The brief to the architects was to create a development that would fit in with the character of Riebeek Kasteel. The architects developed an architectural language of simple forms and a limited palette of materials and colours. Each house has an interface with the street, something which is typical in this Swartland town. A play with heights and volumes create an interesting skyline, and all the units have wide verandahs onto private outdoor spaces.

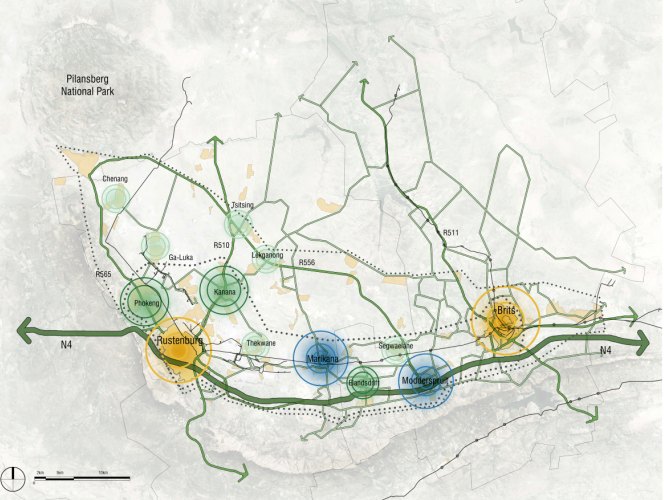

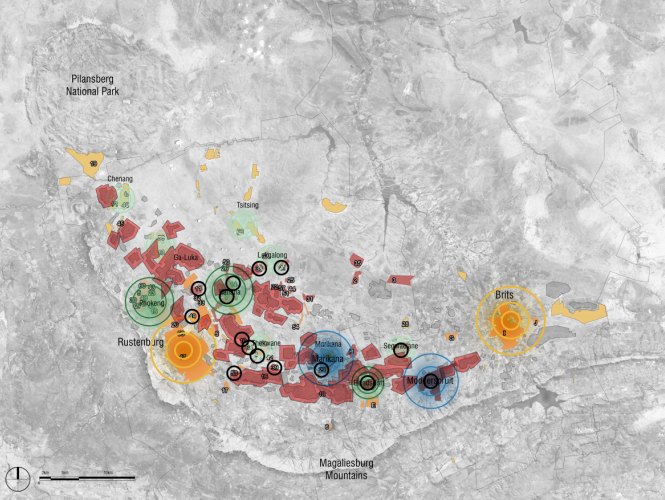

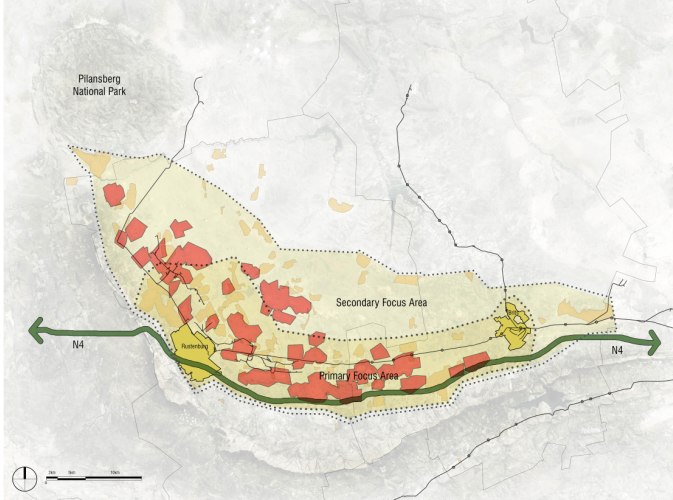

The main intention of the Human Settlement Transformation Plan was to:

- Define the status quo and the challenges and opportunities of the focus area through institutional and contextual analysis;

- Provide a broad analysis and contextualization on mining town’s human settlement challenges;

- To develop an overall urban framework that integrates the findings from the Contextual Analysis with recommendations for the health, sustainable human settlements in the mine areas, based on a visionary concept.

The goal of Spatial Transformation is to achieve inclusive, liveable, sustainable and resilient cities.

Breaking new ground principles implemented:

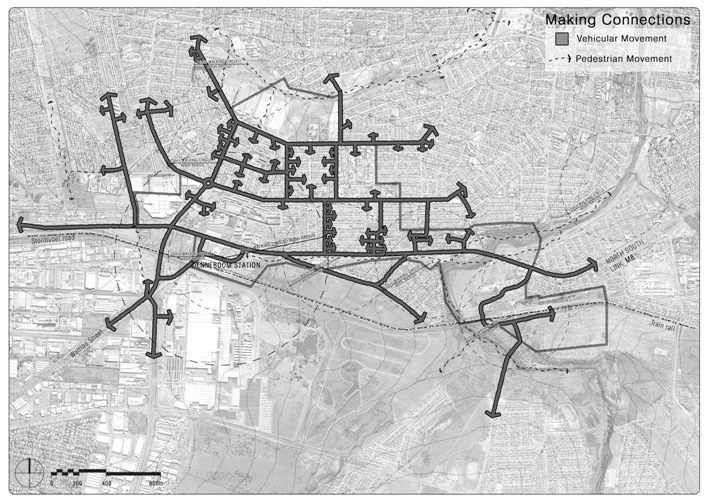

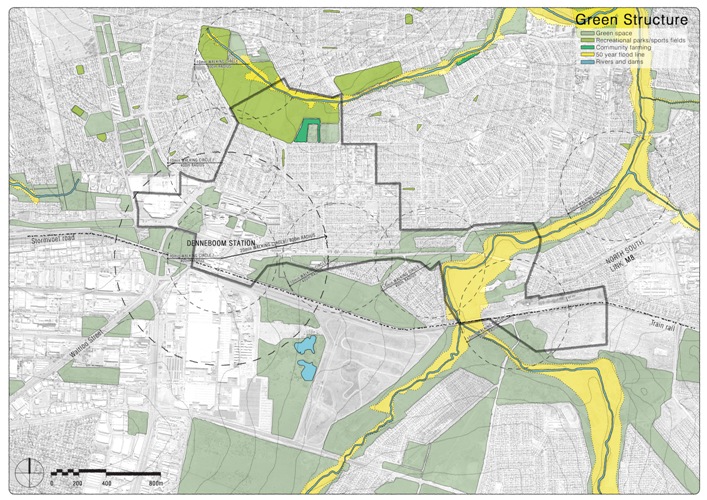

Making Connections, physical and visual integration of spaces

- Balanced Movement Network

- Places for People,

- Mix Uses and Forms

- Work with the Landscape

- Community Life, full range of accessible local services

- Densities, higher density levels to support urban services

- Informal/Formal Trading Spaces

- Parks and Squares

- Manage the Investment

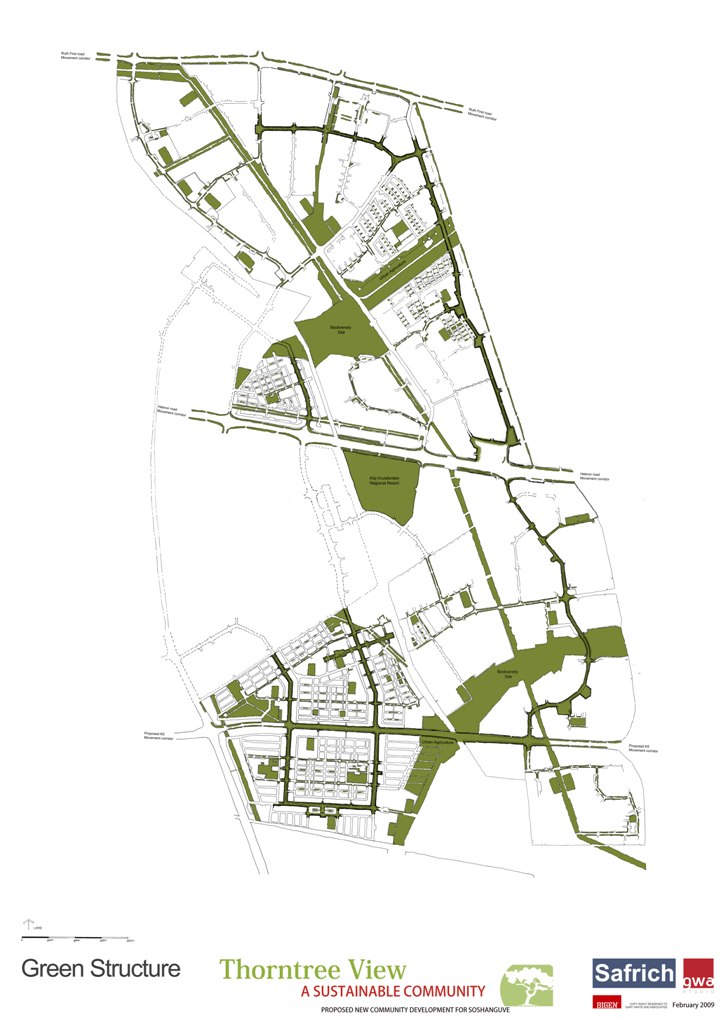

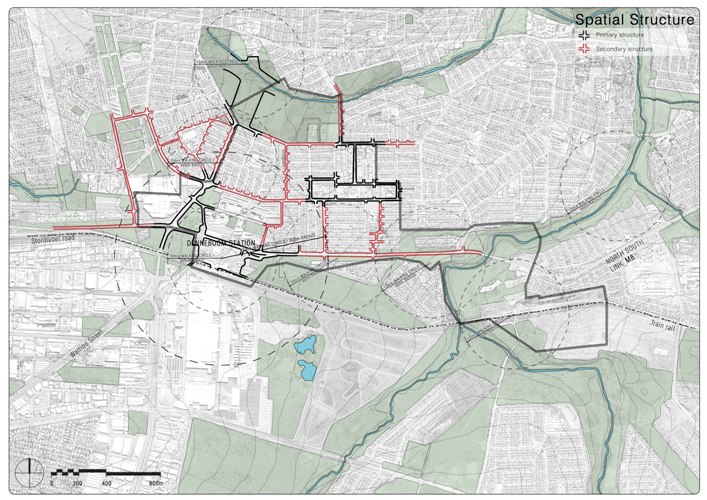

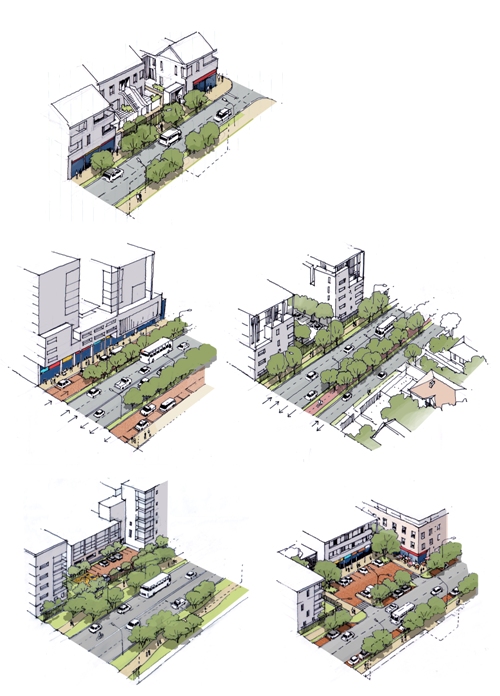

Urban Design inputs are required as part of the Neighbourhood Development Partnership Grant (NDPG) project in the City of Tshwane. Several urban upgrades, and catalyst and strategic projects were identified as focal areas for the wider Atteridgeville Township and Mabopane/Soshanguve areas in the NDPG Business Plans for the City of Tshwane (Respective Business Plans for Township Regeneration, all dated Febr 2012). The Business Plans for these areas identified nodal development around specific projects as spatial mechanisms through which to create the right climate for economic investment and development. The Urban Design input required to develop each node forms part of a first phase, and does not include architectural designs, nor construction and capital investment. The aim of the required urban design input is to develop urban level concept designs to guide phased nodal development and aid in providing more detail for costing and implementing purposes.

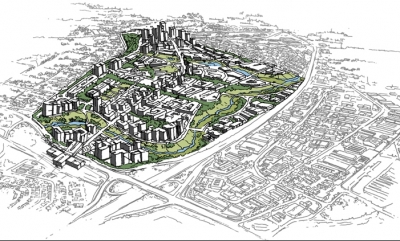

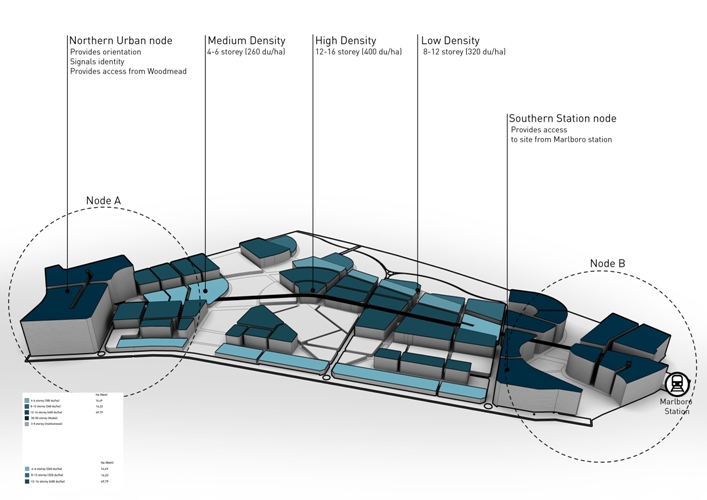

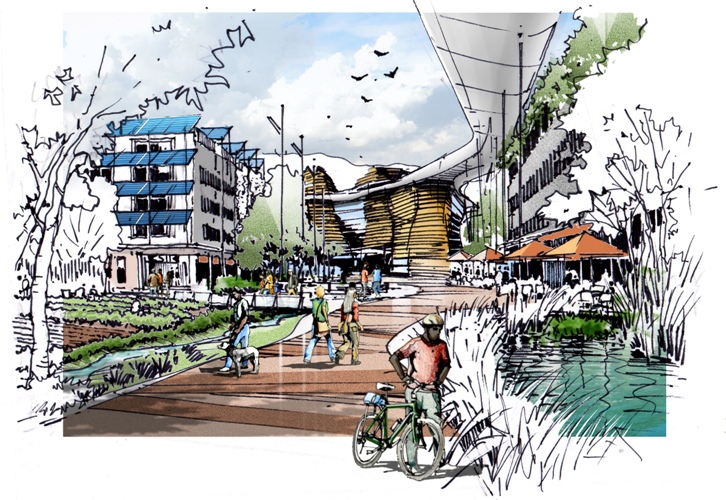

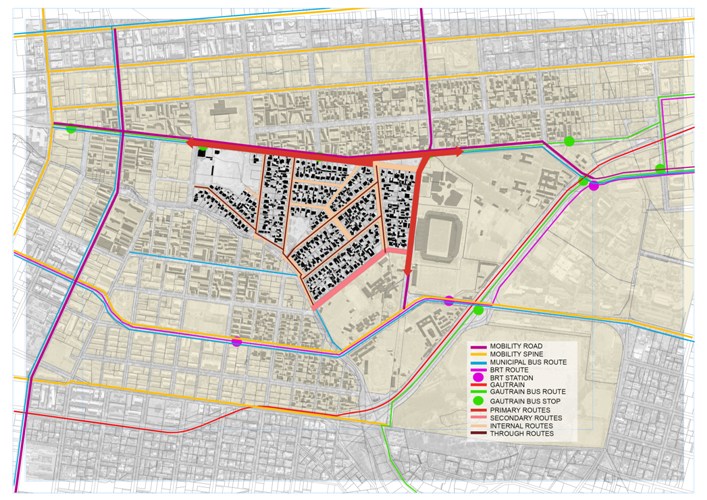

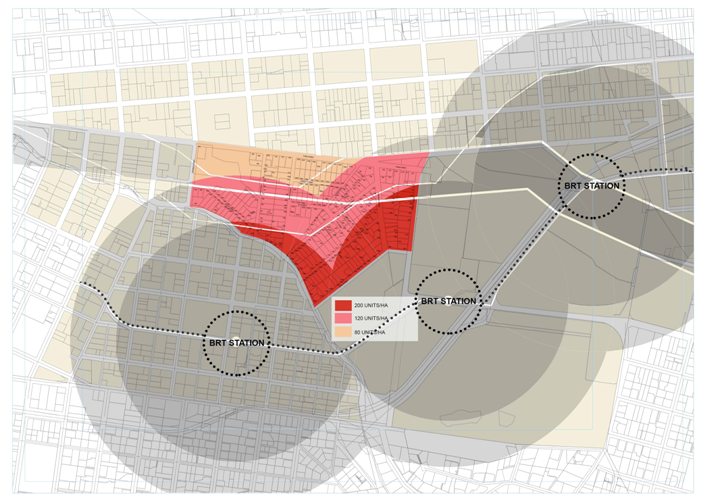

Frankenwald epitomises the art of reconciliation on many levels and scales: -physically by the position of the new development between two metropolitan cities in the economic hub of the country; -economically as the missing link for new opportunity between the high earning hubs and the hinterland of low-income communities with limited economic choices; -socially by providing much needed infrastructure and affordable housing to said communities but also as a money generation project for the higher education institution that owns the land (a highly politicized and pressured environment in South Africa at the moment); -environmentally as a responsible development that integrates natural resources as essential design elements.

Designed to incorporate the need of the community in the present as well as the vision for how future cities must function, this development embodies the argument that density is an asset. Countering the sprawl that unfortunately all around, and linking up to the burgeoning public transport routes (of which the Gautrain is the most significant – a high-speed train route connecting major urban hubs, and scheduled to expand) this development will have a significant impact as new urban precedents for South Africa.

The project for the taxi facility was approved by the NDPG programme of National Treasury along with the adjacent boulevard as part of a phased implementation plan.

The position, diagonally opposite the existing Tower Mall in Jouberton and along the major taxi route of Jabulani Street was finalised subsequent to presentation to both Council and National Treasury after several options were considered. At the time of developing work stage 2, presentations were under way with the local taxi association.

The taxi facility aims to integrate a variety of taxi related uses. It is designed to be a well accessible site with multiple options for traders and visitors to use the space. The facility aims to be vibrant with colour, ample shading from both built roof structures, landscaping and the planting of trees.

The facility can accommodate approximately 60 taxis (or more during peak times in ancillary pockets), with multiple open/shaded areas for which trading can take place. Ancillary accommodation includes ablutions for the public, 3x office, meeting room, kitchenette, toilet and reception area for taxi association’s use.

The Thaba Ya Batswana urban development is set along the confines of the Klipriviersberg Nature Reserve. It straddles the foot of the northern hills of the reserve, bordered by the N12 highway to the north, the R59 highway to the east, and the N1 highway to the west.

The envisaged development, roughly 180 000m² in total, will house mixed use typologies, with a combination of working and living environments. Given the unique setting, guest houses, hotel and conference facilities will form part of the proposed development. Retail and offices will be combined as business parks.

As a result of the distinctive natural setting within the urban environment, sensitive mitigation between the landscape and the proposed new development is central to our development approach.

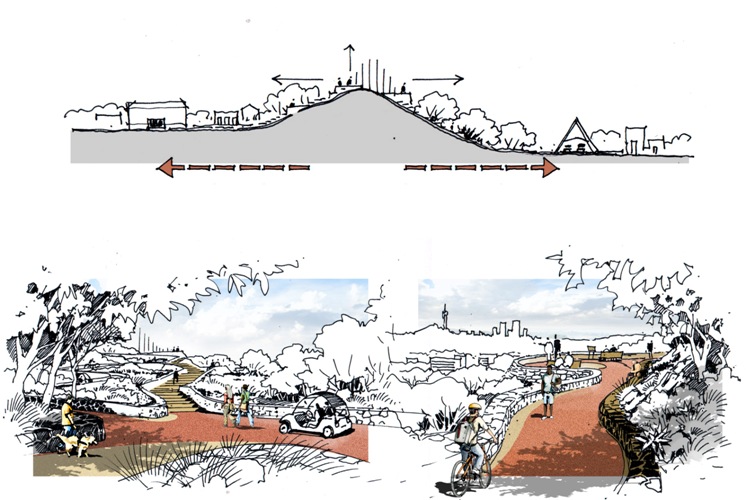

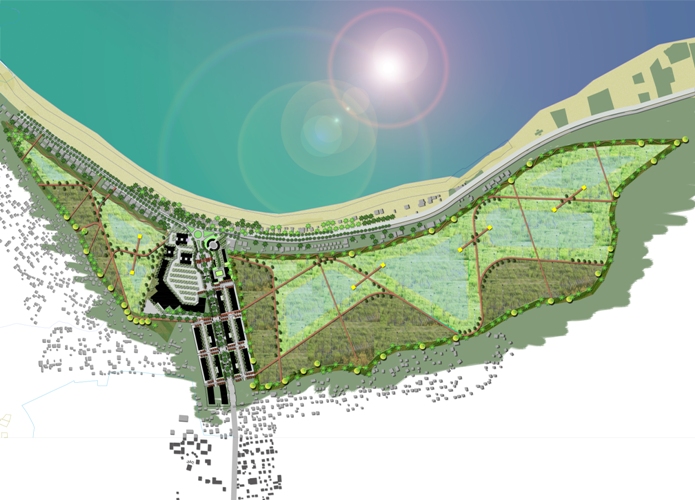

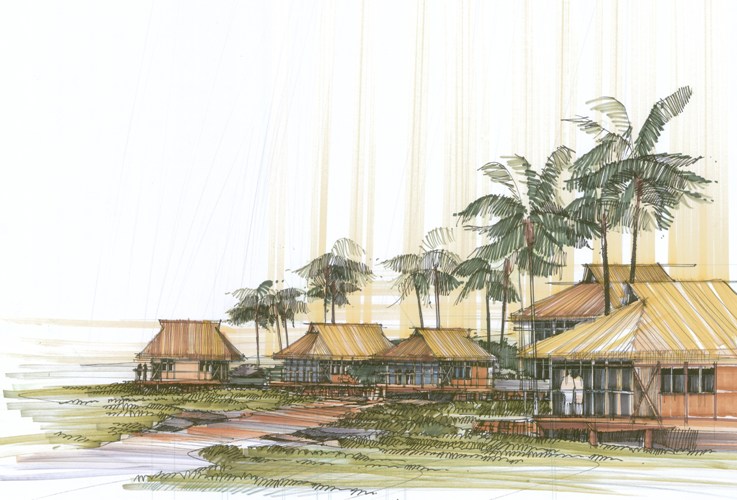

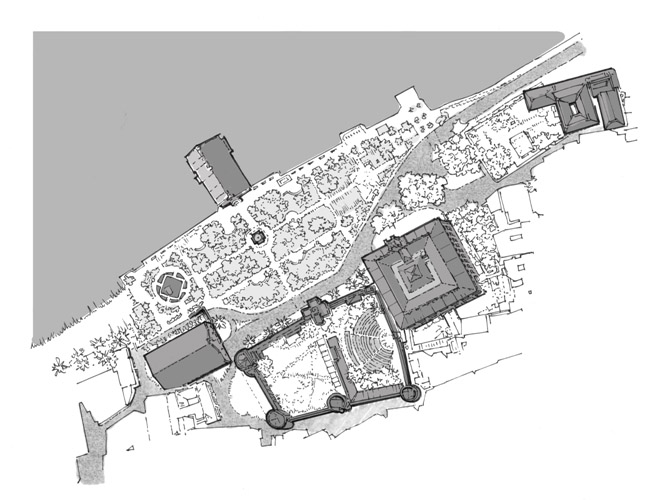

The brief called for Holm Jordaan to assemble a group of professionals and specialists in order to investigate and design an agriculture, tourism and harbour based mixed-use development along the Rio Bengo River.

The Rio Bengo mixed-use project is located 25km north of Luanda along the coast at the mouth of the Rio Bengo River and with access from the northern road to Barra Do Dande. It presents an excellent opportunity to build facilities that will be capable of facilitating a large and sustainable fishing industry in Luanda and Angola. Such a harbour will have all the facilities and requirements needed by a commercial fishing harbour to attract tenants that will fill and operate the space. It will also enable the development of a world class waterfront development around it.

The site was analysed in terms of its physical, social and economic attributes as well as the opportunities and constraints of the site. This first broad concept was done as a desktop study based on existing information and is continuously being updated with input from the developers, financiers authorities and the community as well as information from site visits and physical investigations.

The development comprised a house, art gallery, artist studios and a cottage, spread over 3 erven. The aim of the project was to stay within the Riebeek Kasteel vernacular of strong simple volumes with wide verandahs and high volumes to deal with the hot and dry climate. A minimalist palate of brick, stone and corrugated sheet cladding was used.

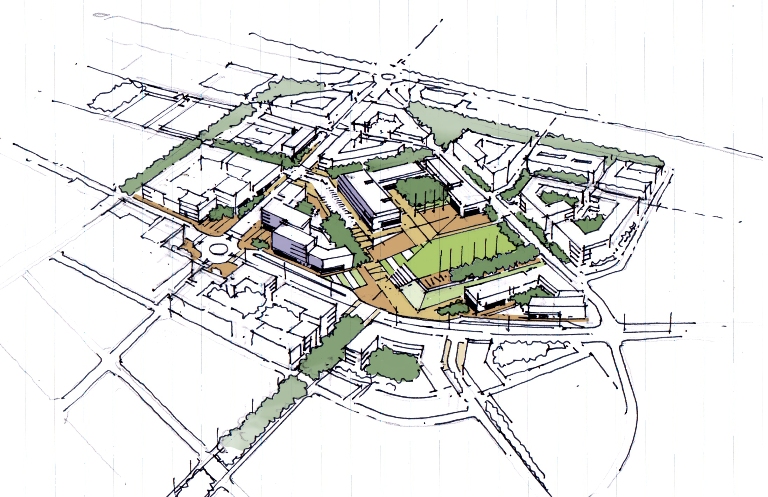

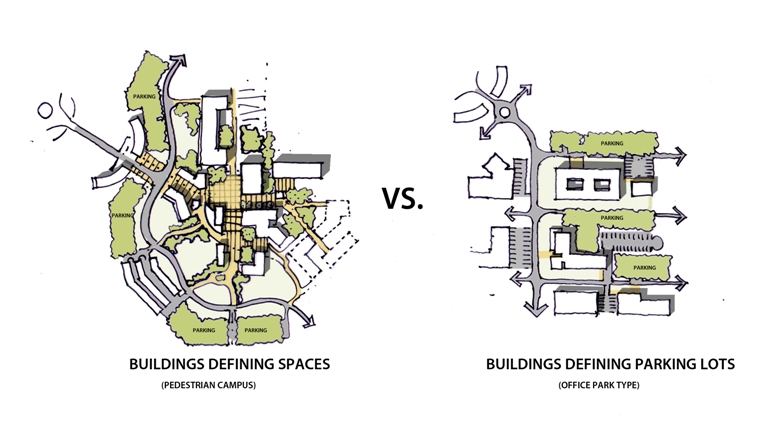

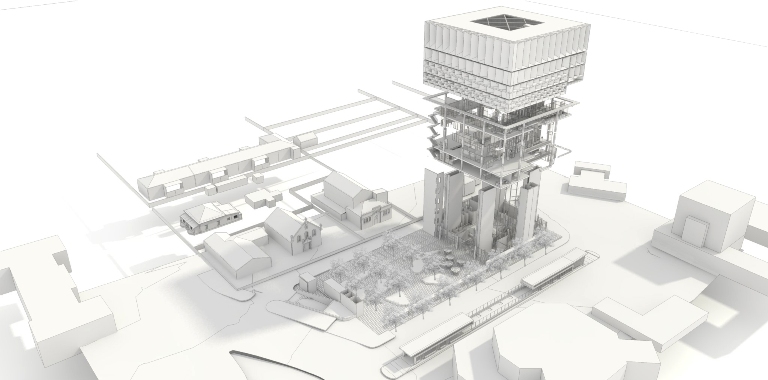

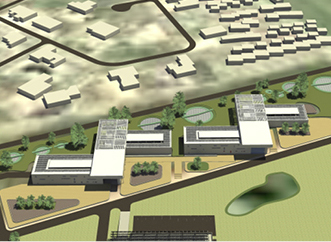

Holm Jordaan Architects and Urban Designers were appointed by the CSIR to conceptualize the vision for the Pretoria Campus. The brief was to envision a unique, intelligent, autonomous, green Campus rooted in South Africa, which expresses the ideals of the CSIR scientific’s endeavours. The key aspect of this statement was the concept of “Campus”, which in essence is a diverse and stimulating learning and research environment that complements all related uses and functions that support it, conference facilities, residences, support shops and restaurants or offices to name but a few. It was important to define this concept as the present condition of the CSIR is distant from “Campus” in its most human, social and diverse meaning. The actual organising layout is rather similar to an Office Park, a strongly vehicle-oriented environment.

Key words to consider are: Campus, human space, diversity, world class facilities, heritage, historical richness, sustainable, intelligent.

Our approach was to define a set of active planning principles that could be applied and guide actual and future development on the Campus and the many disciplines involved in the process. The need for planning principles result from the generally long-time frame in which these projects occur. The vision is therefore related to the intrinsic positive qualities of intelligent human development in the first place.

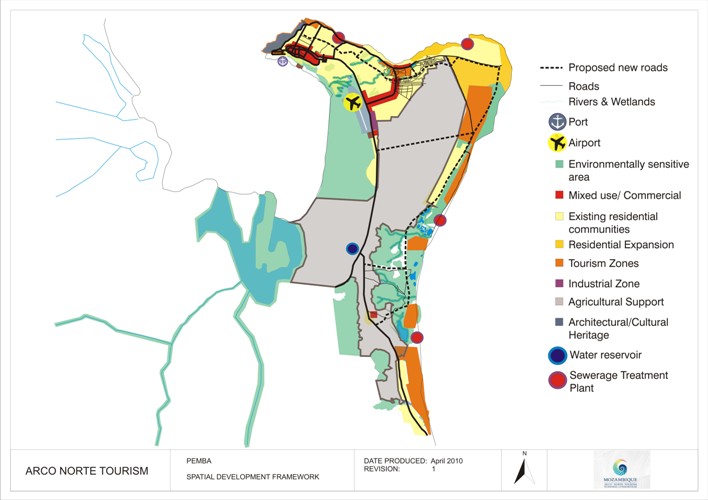

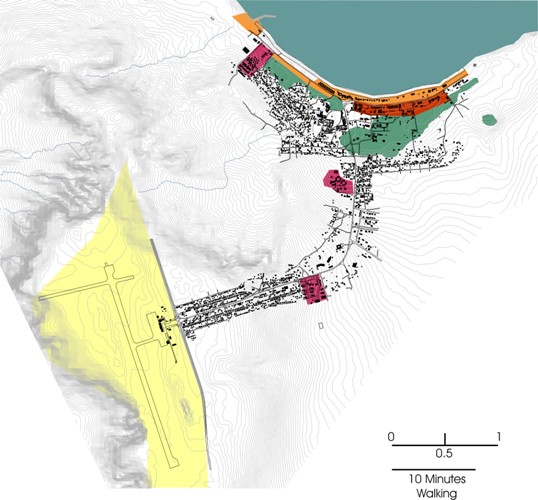

The original brief required the preparation of Master Plans for Potential Tourism Investment Areas (PIA) in three northern provinces of Mozambique. These PIA’s were identified in a previous project commissioned by USAID in association with the Minister of Tourism of Mozambique. That project managed to create interest in tourism development in Arco Norte and set the stage for further investigation and planning. The goal of the Tourism Master Plans is to position Northern Mozambique as a world class, sustainable tourism destination. Through the project it is anticipation to:

- Attract large private investments and partnerships;

- Stimulate tourism related businesses and agricultural transformation;

- Create increased opportunities for employment;

- Contribute significantly to enrichment and empowerment of destination communities; and

- Preserve the environment.

Phase 2 called for Master Plans for PIA’s and the planning for one Pilot Tourism Project within each of the three provinces.

- Master Plans for a total of 17 sites (in three Provinces) that have been identified in Phase 1

- Business Plans for the implementation of three pilot tourism developments (one in each Province).

- Development packages with development guidelines for each Master Plan site with a view to facilitate development in a responsible and sustainable way.

Clydesdale is a low-density residential suburb with historically significant houses located between the neighbouring suburbs Sunnyside and Arcadia. The approximately 270 residential stands have an unique fine grain of mostly single residential units and possess significant architectural heritage – both which is currently under threat of insensitive development. The Urban Design Framework addressed these issues by mapping the issues, opportunities and constraints that has a bearing on the development and/or preservation of the Clydesdale area as well as the urban fabric and urban processes of the study area and the influences of the development pressure present. This included the development vision and concerns of the residents.

The next phase was to address the issues that was identified by reconciling existing and future developments surrounding Clydesdale while protecting the residential area. This was realised by developing a concept for reacting to the opportunities and constraints with intended land uses, street interface, urban form, accesses and movement and by clearly identifying the interface between the developments surrounding Clydesdale and the Clydesdale residential area itself. This framework ensures a future proof planning and management tool for the Clydesdale Residents in order to negotiate with developers, city council and other authorities and to act as a management tool to manage the street quality, additions to buildings, the street interface and future development proposals. Urban Design Guidelines and Development Guidelines was developed to assist in this regard.

This was a refurbishment project for Abalone Lodge, an up-market guest house in Hermanus. The work entailed adding an extra in-situ concrete floor for 5 new bedrooms on top of the existing house, adding a new deck and lounge area at ground level and a complete refurbishment of all existing rooms and bathrooms, new kitchen and a complete re-paint of the outside areas.

There were also additional site works including a new parking area, a new conservancy tank with a soil pump system connected to the municipal sewer, and new landscaping. In addition to the above, the guest house was fitted with a state of the art green technology water and space heating installation. This incorporated two 16kW inverter heat pumps supplying hot water to both the 900 litre hot water cylinders and the hydronic underfloor and towel heating system for each room. The heating system is managed and controlled via a control panel linked to a manifold system with thermostats in each room. The hot water requirements were further augmented by solar panels.

The project was of a very complex nature as it was an extensive intervention which incorporated the existing building with numerous structural challenges. Further to that, the client requirements in terms of quality of finishes were very high.

Holm Jordaan Architects and Urban Designers were appointed by the CSIR to conceptualize the vision for the Pretoria Campus. The brief was to envision a unique, intelligent, autonomous, green Campus rooted in South Africa, which expresses the ideals of the CSIR Scientific’s endeavours. The key aspect of this statement was the concept of “Campus”, which in essence is a diverse and stimulating learning and research environment that complements all related uses and functions that support it, conference facilities, residences, support shops and restaurants or offices to name but a few. It was important to define this concept as the present condition of the CSIR is distant from “Campus” in its most human, social and diverse meaning. The actual organising layout is rather similar to an Office Park, a strongly vehicle-oriented environment.

Our approach was to define a set of active planning principles that could be applied and guide actual and future development on the Campus and the many disciplines involved in the process. The need for planning principles result from the generally long-time frame in which these projects occur. The vision is therefore related to the intrinsic positive qualities of intelligent human development in the first place.

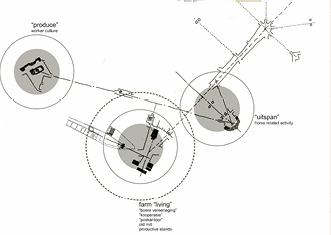

Verkykerskop is located along the Free State Provincial tourist corridor (M3). Characterised by scenic natural topography with ancient rock formations, ancestral rock paintings and prominent farming history, the area is also nestled between commercial and small-scale subsistence farming. The proposed new development is carefully inserted between farmland, existing buildings with dormant infrastructure, livestock and horse holding areas, gravesites, lookout points and watersheds. The “uitspanning” - a local word meaning space to relax and unwind after long migration with livestock - is proposed as the main node and public space, at the centre of the 43-ha site. The noble program of 300 mixed income residences, most with own intensive home farm opportunities is matched by a broad complement of civic uses. Adaptive reuse of existing buildings and structures allow the area to re-emerge and participate in the regional economy. The balance between built and open spaces at Verkykerskop does more than facilitate pleasant communal living. It integrates human development with sustainable agriculture, energy farms and environmental management. The plan allows the built structures and fabric between open spaces to nestle in the natural and cultural landscape. The master plan sets in motion the essential creation of public opportunities to live, work, farm, learn and play in direct response to the natural queues of location - land, local vegetation and prominent views.

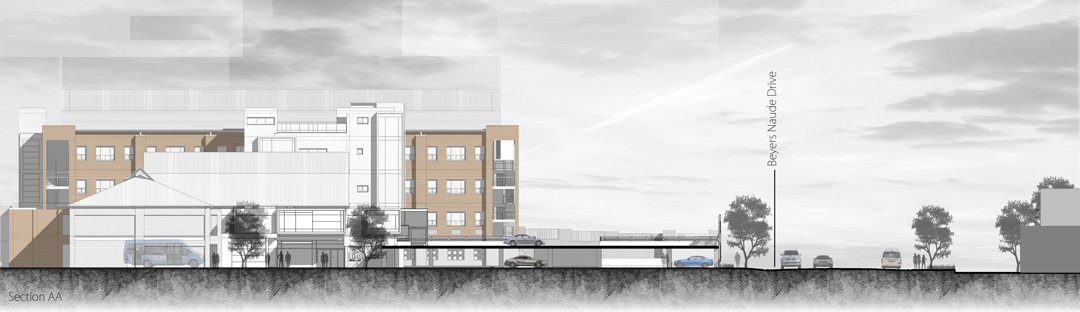

The brief called for the design and upgrade of the Peglarea Hospital and takes cues from the existing building. Space is required for an extra 59 beds and a new operating theatre. A new face is given to the existing building by means of a parking garage. To form part of this the entrance lobby is upgraded and a new coffee shop is added.

Along with Demacon, Holm Jordaan Architects and Urban Designers were initially appointed by BIGEN AFRICA to assist with urban design proposals in support of the Neighbourhood Development Partnership Grant (NDPG) submission for the Steve Tshwete Municipality, Mhluzi, Middelburg in Mpumalanga. The proposals are aimed at improving the living standards and social conditions of the Mhluzi community. A number of development upgrades were identified for the urban framework as part of the NDPG programme, namely:

Area A – New central development node

Area B- Upgrade of the existing Mhluzi node

Area C – Development and expansion of the new social/community node

Area D – Light industrial node

The sports node and a new entrance node

Holm Jordaan was subsequently appointed for the design and implementation of three nodes. Besides a park with extensive multi-purpose needs, the specific focus of the project was the upgrading of public spaces and public amenities.

Major design considerations include robustness, permeability and also visibility. Forms allude to Ndebele place-making, while being brightly colored and unpretentious. In each case, a simple raised podium forms a datum to hold the functions in considered relationship to another. Each function is expressed as a different form. While each form has its own concrete roof, a light-weight second roof floats over to create shaded in-between spaces. Lessons were learnt from local architect Peter Rich, and also from the work done elsewhere in Africa by Finnish architects Heikkinen-Komonen.

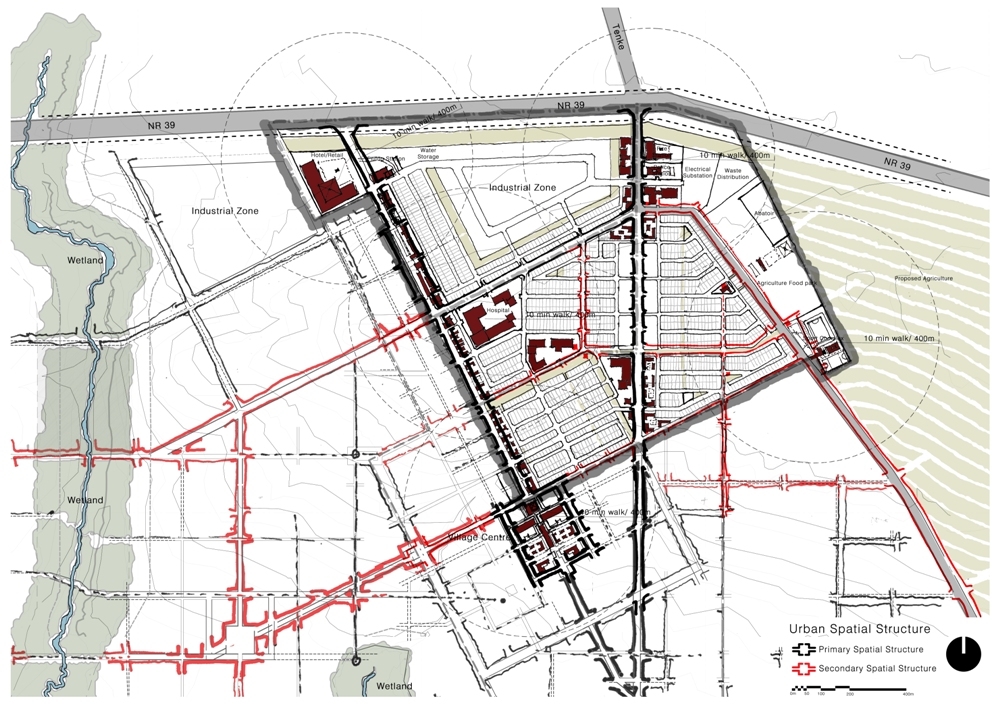

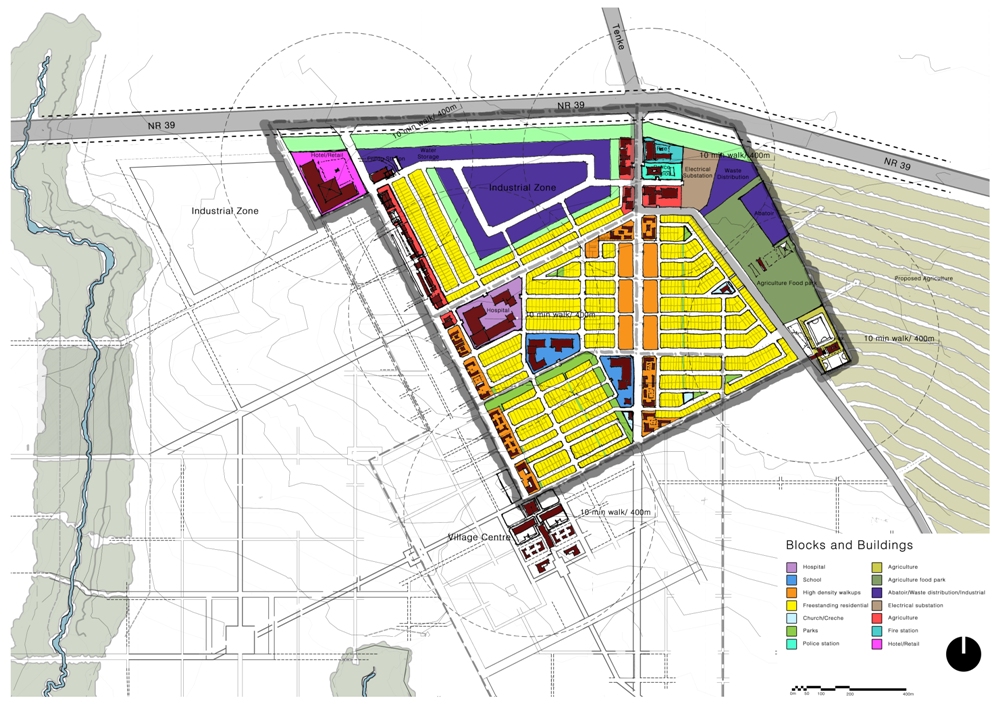

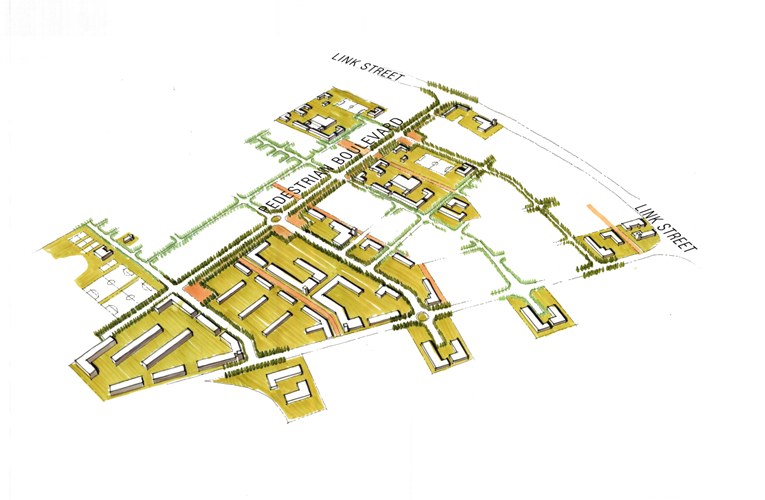

The Design of the New Town Development is conceived as a sustainable and well connected urban Precinct. Natural green and agricultural landscapes as well as the mining industry is integrated with the urban built form generating a positive transition of urban transect.

Keeping in mind the large scale of the proposed town, the development is divided into phases, but a larger vision with a strong urban core is proposed. This urban core is rotated off axis to strategically meet main arterial routes. Secondary urban centres are proposed within the future phases, forming a system of public squares and positive nodal development. These urban centres house public and commercial spaces like public squares and markets.

The development is thus conceived to create an important regional node along the NR39 route which connect the two existing towns. The intent is to create a walk-able sustainable community within the node. The urban design is thus generated from the local context allowing for greater connectivity with the neighbouring precincts on both a venicular and pedestrian scale. Alternate forms of mobility is considered within the urban layout allowing for pedestrians, cyclists and bus routs.

The Refilwe nodal transformation forms part of an urban network of upgrades supported by the Neighbourhood Development Partnerships Grant, National Treasury, in the Metsweding area, City of Tshwane. A small, humble urban intervention, this upgrade is an example of a local community taking great pride in the renewal of public space.

By simply formalizing open space through provision of a permeable edge condition and patterned surfacing, the area in front of various small existing shops was upgraded. An open-ended, covered area along the new periphery houses basic amenities of public ablution, water, roof shelter and seating – while leaving a framework for a series of flexible programmatic interventions, such as a car wash, waiting areas for taxi drop-off, hawkers’ accommodation and so on. These functions are arranged along a raised platform. The plinth gives prominence to the otherwise mundane functions accommodated along the edge. Along with patterns recalling local tradition, Maraba-raba and chess play boards are part of the horizontal field that binds the spatial diagram together.

Robustness in design drove overall outcomes. As a result, apertures are screened off, but no glass panes were included and all sanitary ware was done as stainless steel, with hidden fixtures. The brick screens also assisted to create a building interface with no “front” and no “back” – usually a challenge given the programmatic requirement of public ablutions in such a central location. Bright colour gives new identity to the small urban hub.

The local community was involved in the construction of the project and has taken great pride in this small, colorful intervention. The area defined in front of the existing shops recently became a space for protesting linked to service delivery. Not a single building or structure was damaged during these violent protests, attesting to the ownership taken by the local community.

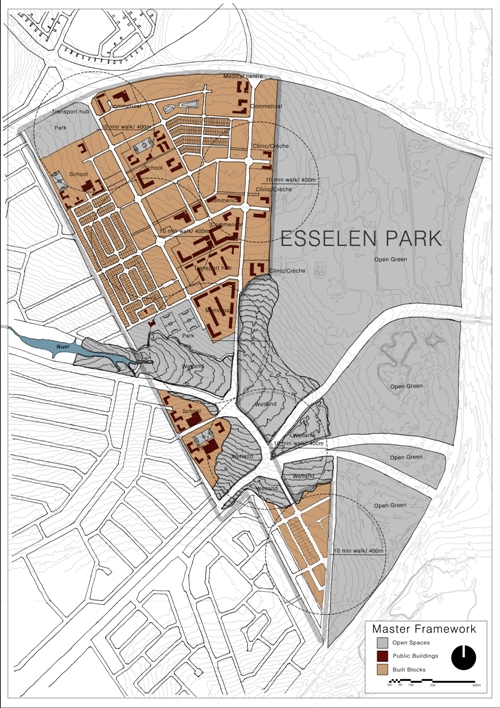

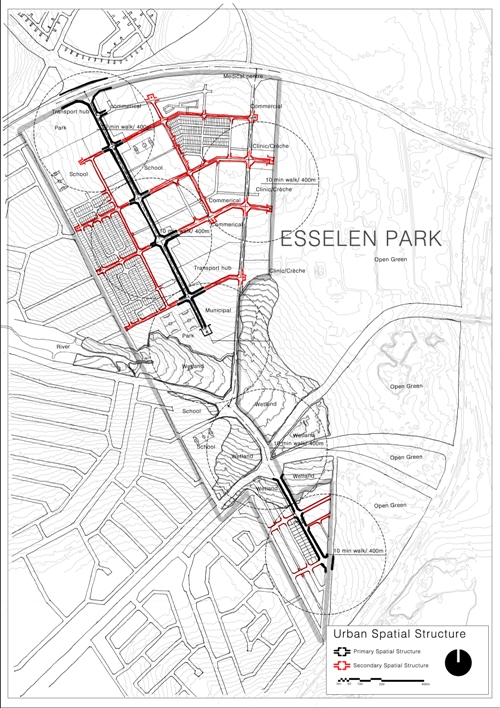

Esselen Park, located between Tembisa and Kempton Park is a proposed mixed use urban development possessing numerous public. The broad mix of uses and amenities, offers a variety of choices through the provision of social, civic, community, recreational, retail and business facilities within close proximity.

The development provides a unique South African urban hub that is based on traditional town planning notions of mixed use, connectivity, integrated open street systems and clearly defined public and private domains.

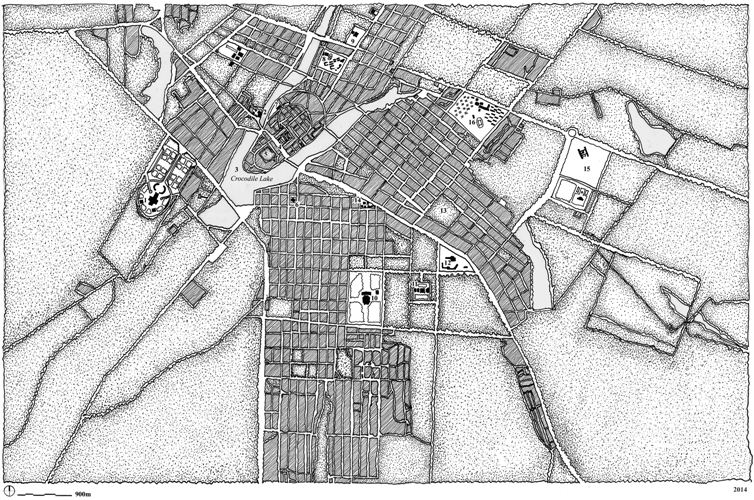

Africa Drawn: One Hundred Cities is a collection of drawings that explores one hundred of the most connected and significant cities of the continent. Urban spaces were documented to illustrate contemporary and historical place-making actions of people. The study attempts to provide a resource of special and figure ground patterns that depicts the diversity of urban form, by providing a spatial point of departure for all practicing and interested parties acting in Africa.

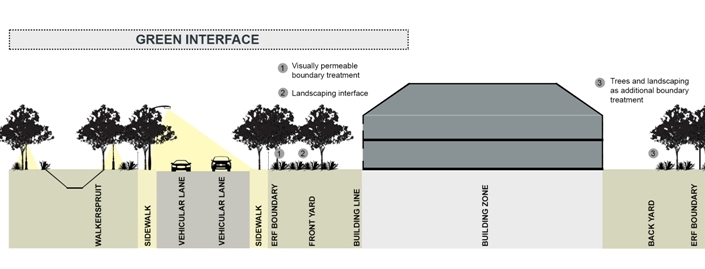

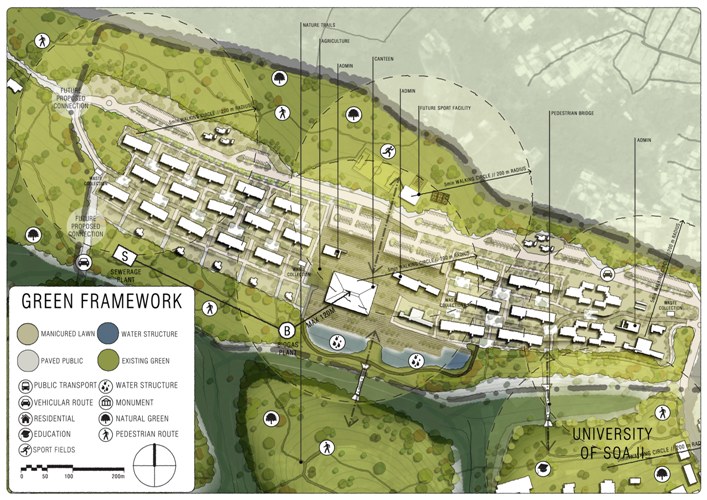

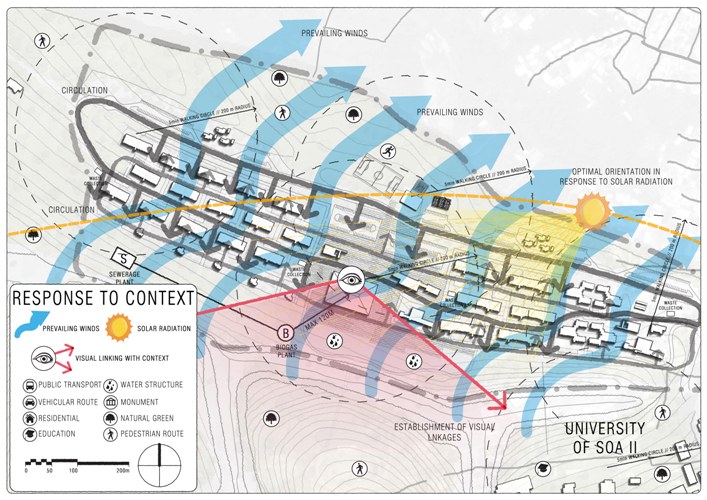

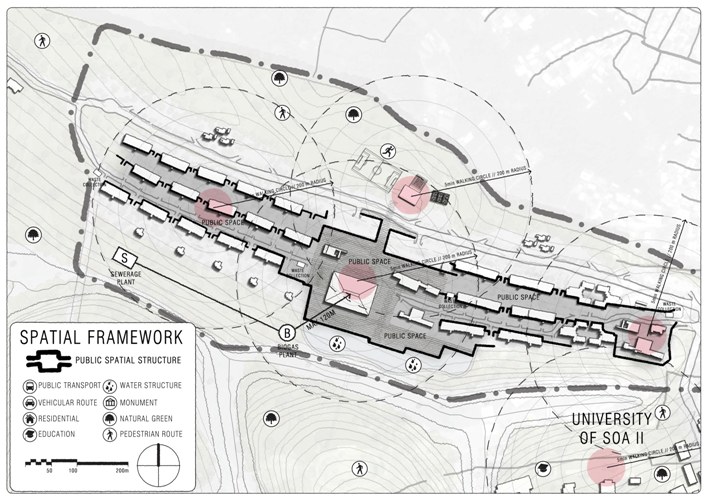

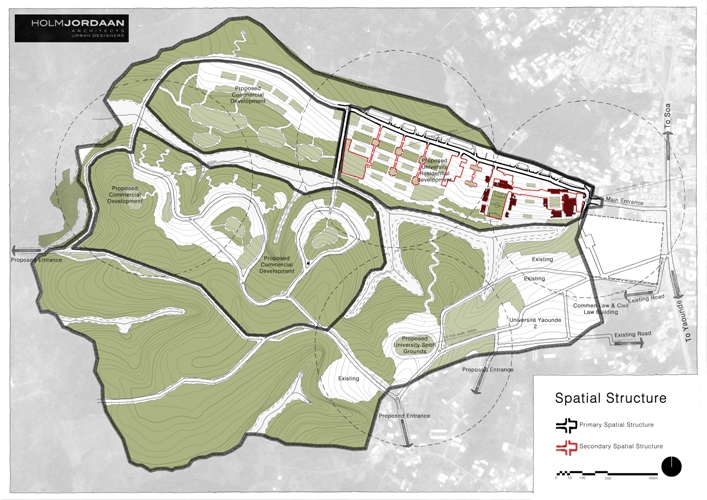

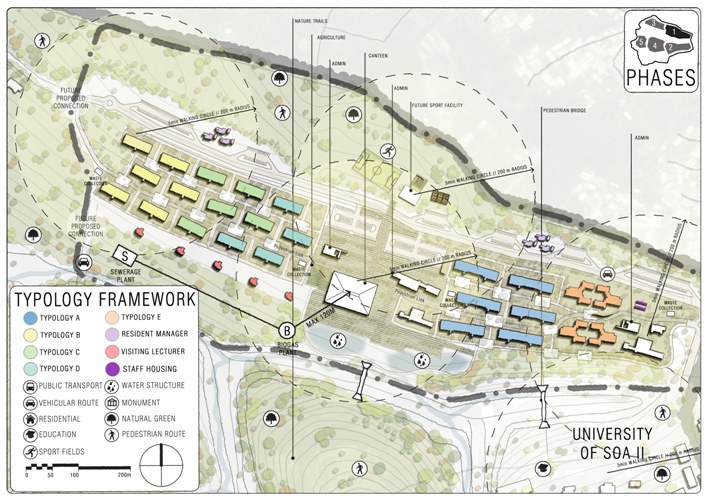

The brief called for the design of student accommodation for 2 500 students on the University of Soa II - Yaoundé campus in Cameroon. The site is located near SOA next to the existing University of Yaoundé campus.

The design of the accommodation facilities campus is conceived as part of a sustainable and well connected campus. The proposal is strategically located to integrate with the existing campus facilities as well as provide scope for future development.

With future expansion in mind, the development is divided into phases, with the student accommodation facilities as the first phase. The layout is strategically developed to accommodate views over the gorge and provide a layout conducive to air/breeze movement through the various buildings. The buildings are oriented to optimise the exposure to natural light and protection of sunlight in the hot and humid tropical climate. The new proposed development is linked to the existing campus with pedestrian bridges to facilitate crossing the gorge.

The first phase includes student accommodation for approximately 2 500 students including the complimentary facilities such as a canteen which can accommodate 3 000 meals a day, an administration block, provision for a future multisport facility as well as accommodation for the resident managers and visiting lecturers.

The facilities have been strategically located within comfortable walking distances. Further connections have been made to facilitate vehicular access and a future ring road to facilitate connectivity/accessibility throughout the campus.

The narrow site for this medical pavilion (200m2) faces onto one such sea of parking to its immediate north (belonging to the Wilgers Hospital), with residential buildings along all remaining sides. The massing and placement on site were determined by the balance between an extremely tight budget, FAR and said parking regulations respectively, followed by the rest of the opposing forces described above.

The medical pavilion was positioned to edge tightly along the northern boundary of the site, with cars tucked away neatly behind. A double volume defines the entrance, dramatically framed with the corner articulation that responds to its ambition of becoming a small landmark. The pavilion takes cues from the architectural history of Pretoria. Envisioned as a stoep with a pergola to its north, the consulting rooms are placed at the centre of a constrained envelope. The exterior is bagged and painted white (another nod at local traditions), with a smooth interior finish. Local materials were used as far as possible, with furniture pieces hailing the city figure-ground, whilst responding to the notions of ethics of medical practice rather than simply aesthetics. As such, an environment that embodies an embracing, warm and therapeutic sensibility underpinned all decisions in the choice of careful detailing. An urban roof garden, again hailing the distant urban history, creates a small sanctuary. A carefully considered screen that will ultimately become a green screen softens the proximity to road and parking lot onto which the building faces, whilst binding the northern façade. It also mitigates the climate of the interior of the building, along with sliding screens that were again the result of a meticulous design process.

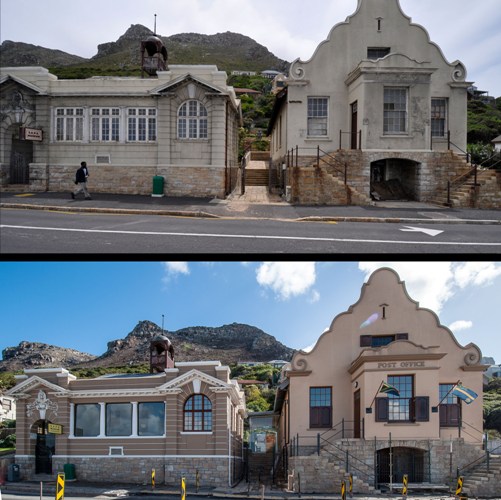

A contemporary intervention, linking two historical buildings of different architectural languages. Situated along the Muizenberg scenic mile, the Police Museum is a significant part of the local community and considered by many to be one of the historical highlights of the conservation area. After many years of neglect, the two buildings housing the Police Museum have fallen into a state of disrepair and the project team was appointed to restore and refurbish the buildings, making them compliant with current building regulations and to make the facility universally accessible in line with Government Policy.

The first building, built in 1910, was the one and only Carnegie Library in Cape Town (one of eight remaining country wide). The second building on the north side of the library, built in 1912, was a post office, the first to receive airmail in South Africa. When the police moved into their new premises during the early 1990’s the two buildings were converted into the Police Museum.

Heritage indicators for the project called for the later architectural clutter to be removed, and the need for sensitive contemporary interventions which were to be implemented with an understanding of the proportions, scale, spatial and architectural character of the two buildings. Furthermore, the aesthetic character of the existing and surrounding historical buildings could not be diluted.

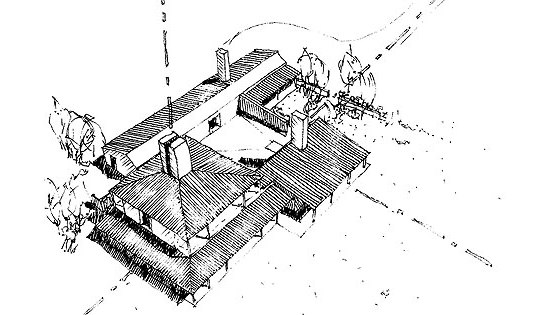

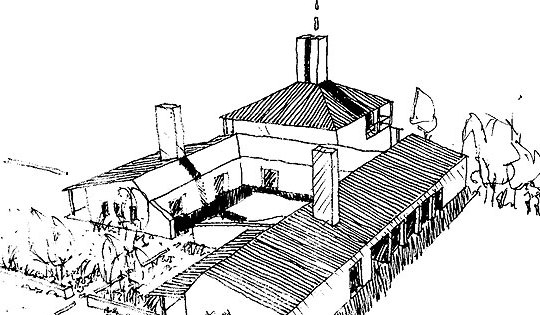

To form a contemporary residential building born from “old Transvaal” architectural principles. A cluster of buildings are grouped around the central “bakoond” or courtyard as if they were timelessly added over a period of time.

Living under canopies of sheltered roofs with close proximity to the landscape is achieved through spatial planning and regional construction and material usage.

Think “bakoond”. This red clay brick outdoor room filled with the smell of freshly baked bread and brewed coffee on a crisp Highveld morning. As central welcoming courtyard space it is both entrance, transition space and a place of prominent contrast between building and the natural landscape beyond its enclosed confines.

With seasonal white canvases that shields guests from the African sun and exposes a bright blue sky of this “rural setting” its festive qualities is at the core of this home. Horizontal and vertical patterned red clay brick plains enounces axial views towards safe comfortable living spaces, green pastures beyond the articulated red façades and an ever changing sky. A true datum for landscape, building and residents to meditate and celebrate life.

An hourly change is brought about to this distilled uniform outdoor space. Deep reveals of passage and movement exposes both the program and activity of adjacent spaces. Filled with summer shade and winter light spaces beyond the entrance become a distant focal point of activity and a grassy landscape.

The brief called for the design of a medical cosmetic centre. A clear distinction between the main functional tiers of the program was an important requirement from the outset, while bearing aspects of privacy, visibility and security in mind. Besides practical considerations, sensory awareness, especially for the spa, had to provoke an exceptional haptic experience.

The corner of Tram and Bronkhorst is celebrated as the major vertical definition in the design, with a triple volume that is expressed on the outside of the building facade. The edges of the site is landscaped as linear water features, recalling the original canal system of the city.

The building footprint edges onto site boundaries closely to create a defined street presence. Given the programmatic requirements for medical facilities, privacy from the street is a major design concern. Therefore, privacy is created while active edges are future enabled in the design of the northern facade. Here, a demountable screen becomes a device for creating privacy while also acting as climatic and security mechanism. Upon entering the building, the spatial experience is enhanced with verticality. A triple volume results in a dramatic entrance lobby and waiting area.

By contrast to the rectangularity of the overall design, the first floor (spa) gives way to a series of undulating walls. These create soft pockets of space on the inside of the building, enhancing the “spa” feeling. Hints of this space are made on the eastern and western facades.

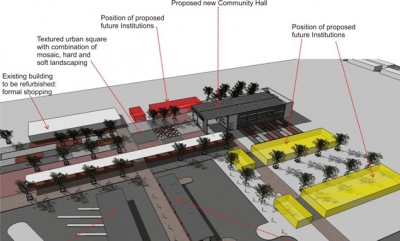

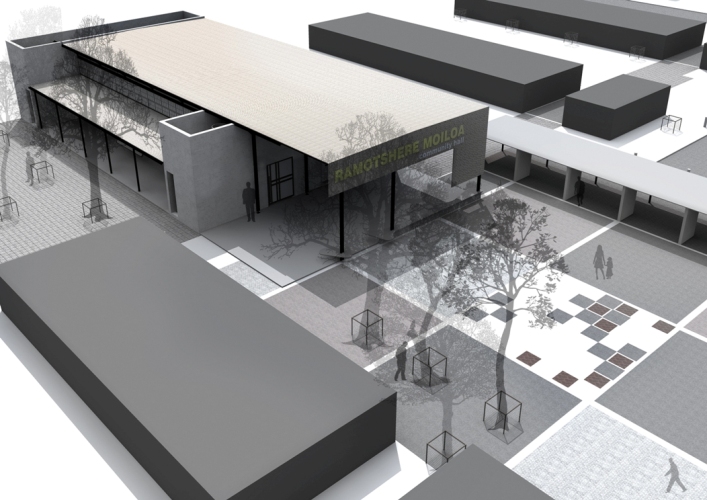

The main purpose of the community hall is to be able to house various community related functions as part of a multi-purpose centre to serve as urban foci for the township. Whilst considering the budget, the hall had to be designed in such a way that it would be robust to accommodate community gatherings, meetings, performances, weddings, funerals and either standing or seated functions. As a flexible design consideration, being able to accommodate indoor sports is a secondary functional requirement. The concept for the community hall is simple: two service boxes hold the multi-purpose area which is articulated in light-weight material as opposed to the “heavy” utility boxes. Colourful polycarbonate sheeting will enliven the lighter multi-purpose area, which also opens to the sides to extend inside-outside space. The building addresses the urban square immediately to its west with an extended roof which also acts as defined threshold to the building. The overhang also denotes hierarchy to the building. The square holds all the functional requirements together in a carpet of textured landscaping to contribute to a meaningful sense of place. Amongst others, mosaic patterns will be created by the local community with a small chess playing area which will contribute to creating a vibrant environment.

The clients are both artistically inclined and have articulated tastes. The brief entitled a modern family home, with generous amount of space that should preferably act as individual platforms to exhibit various pieces of art. The beautiful view should ideally be incorporated with-in each structure, with elements specifically framing the vistas beyond. The transition between home and landscape must be gradual, yet cohesive to the overall design.

This residential project is derivative of House Langenhoven (by GWA Studio, Pretoria) which is situated on the Irene Farmsteads in Pretoria. The concept of House Bryanston is similar to that of House Langenhoven, with the main generator, the fact that it is placed within a suburban city context. The site (with a beautiful view over Bryanston, Johannesburg) allows access to the house from the back. As one enters the site from above, one’s view is directed between the various wings and to the landscape beyond, as if one is wandering on a farm landscape.

The house is split up into various wings, with the central wing acting as the public point of access, with a northern wing to the left, and a southern wing to the right. The northern and central wings are connected by means of a partially covered stoep /veranda, whilst the private sleeping realm selectively connects physically and visually to more private landscape and balcony areas.

The various wings each represent different functions and accommodations. Thus each wing is tectonically responsive to its programme, and allows for related tectonic differentiation. The various structures function as a small village on a city scale. Articulated and well defined interior/exterior and landscape cohesively stitch together the individual character of each wing into a single form.

The house and its various structures are divided into four wings. These wings are strategically placed to inform the accommodation to house various functions/grouped activities. These patterns of intimacy gradually allow each structure/ wing to react as a single entity, whilst glass walkways subtly connect them as a cohesive whole.

The architectural iconography is derivative of farm style living. Certain wings open extensively to utilize as much exterior space as possible, connecting interior spaces with one another. This residence and its design resolution is first and foremost informed by the prominent slope, where public entities are placed hierarchically on the highest contours, whilst more private accommodations are placed lower, to incorporate exterior facilities such as verandas, other exterior rooms and landscaping elements.

The brief intent was to implement a new Control Centre for the Integrated Rapid Public Transport Network. The facility has a staff and personnel contingent of approximately 103 people who represent different departments involved with the monitoring and control of the RRT system as well as security, operations, traffic, emergency and fare collection. The building also houses the spatial requirements for the technical and operational spaces, rooms and shared facilities i.e universal access, wayfinding, rest/locker rooms, climate and general indoor environmental quality. Located on the corner of Joubert and Nelson Mandela Streets, the new intervention is designed to be an urban landmark, celebrating its context as a new addition to a historic precinct. The RRT TMC claims a presence within the surrounding context and provides accessible services within the community. The public interface is designed to promote an active urban edge along the boundary of the building envelope that faces onto Nelson Mandela Road as well as the urban square. Sustainable practice has become an international, non-negotiable premise for the design of progressive buildings. Given the recent energy shortages in South Africa and rising cost of energy; both philosophical guidelines and specific practices should inform an environmentally responsible design philosophy.

The new Visitors’ Pavilion is a simple platform with several smaller pavilions that define the architectural space in between. Visitors would enter by going up a ramp, and due to the slightly sloped site, would leave down another ramp in the direction of the entrance to the Campus, in this way articulating the entrance. A secondary structural system holds the floating roof plane. Given the modernist architectural heritage of the SABS Campus, the pavilion draws from the work of renowned modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe. Similar to his famous Barcelona Pavilion, the space in-between becomes continuous space; blurring inside and outside so that the building does not have a front and a back. The design was premised on an absolute distinction between structure and enclosure—a regular grid of steel columns interspersed by freely spaced planes. The entire building rests on a plinth, while the floor slabs of the plinth projects out, articulating the threshold. Edges of the smaller pavilions give way to round corners, further creating a distinction between rational structure and plastic form. The latter juxtaposition draws on traditional South African forms of architecture. Natural light is applied as an architectural material and was considered from the outset – indirect light washes walls and creates texture, while articulating form.

HolmJordaan was appointed to restore buildings along the western edge of Church Square over a period of 28 years.

Restoration work was done with expert knowledge and skills to conserve the heritage of the Church Square Precinct. The general approach to all restoration work undertaken was to research the original construction methods, materials and applications. Thereafter research was done on how contemporary materials and methods could be employed to match the existing structure without detracting from the authentic building’s appearance and performance.

Previous poor workmanship was repaired, and consequently extended the life of the buildings. Amongst others, the projects included scientific research on sandstone restoration as a common denominator. The chief principle was to retain as much of the original buildings, yet repair the damaged elements with good practice to match the existing as authentically as possible.

Meticulous attention was given to detail. Profiles were measured, and steel forms were made to remodel damaged elements such as facade details. Water penetration prevention was applied to all buildings with details as illustrated in the drawings and photographs.

The Church Square Precinct comprises of the following buildings:

- The Palace of Justice constructed in 1899 (restoration completed in 1983).

- “Ou Raadsaal” constructed in 1889 (restoration completed in 1988)

- Western Facade (restoration completed in 1990)

- Main Post Office (restoration completed in 2011)

AWARDS:

• Western Facade: Old Pretoria Society certificate of Merit (1990)

Institute of South African Architects Conservation Award (1990)

• ”Ou Raadsaal”: Institute of South African Architects Conservation Award (1991)

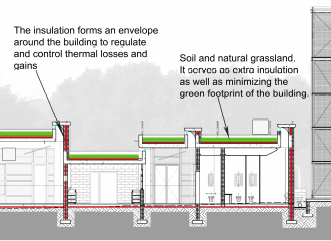

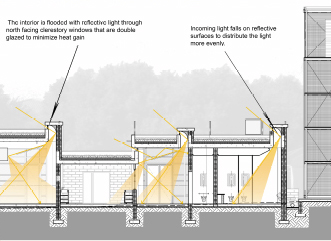

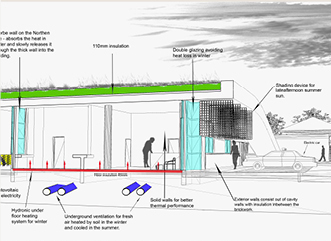

The brief called for a new extension to the VULINDLELA Academy that would accommodate breakaway rooms, training rooms and offices. In essence a very simple rectangular pavilion, the new addition responds to both the scale and layout of the existing training facility. The form steps to accommodate the angular site. Functions are lined along the edges of the open courtyard, accessed from an outside covered area.

While the flat, planted concrete roof has thermal advantages, it steps to allow light to filter into spaces. Rain water is harvested for internal use.

A structural grid of 5 x 5m is used for the new building. This allows for an ideal building width to accommodate environmental control, structure efficiency and space flexibility. The layout, insulation, window size and orientation, shape and proportions have all been optimized in order to use least possible external energy for thermal comfort. Reduction of need for air-conditioning is afforded by passive design and fresh pre-cooled/heated air supply, reduced load through energy efficient equipment, under floor heating through a solar heater and lastly solar cooling with an air ventilation system.

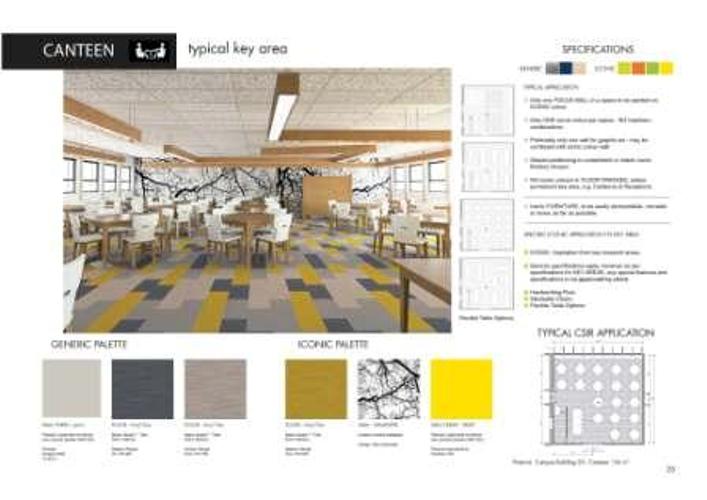

Holm Jordaan and Omnibus Engineering compiled an Energy Master Plan for the DBSA campus. Aligned with both international thinking and local circumstances, the DBSA manages its energy usage with the comprehensive Energy Master Plan. The DBSA notes that the reason for this energy master plan is three-fold: to ensure energy security, to reduce energy cost and to promote responsible development. According to the DBSA, imminent developments along neighbouring sites (such as the forthcoming Pan-African parliament) will continue to pressurize the near-by sub-station, further prompting the architect’s green thinking and to include the maximum energy saving options available.

It is furthermore important for the Bank to demonstrate best practice in terms of energy efficiency and generation; as well as small environmental footprint. There are the following steps towards effective energy consumption and a reduced environmental footprint. These include:

- avoidance of wastage,

- reduced consumption by efficient equipment,

- time of energy use,

- reduce consumption by efficient behavior,

- own green energy generation.

Awards: 2011 PIA Award of Merrit

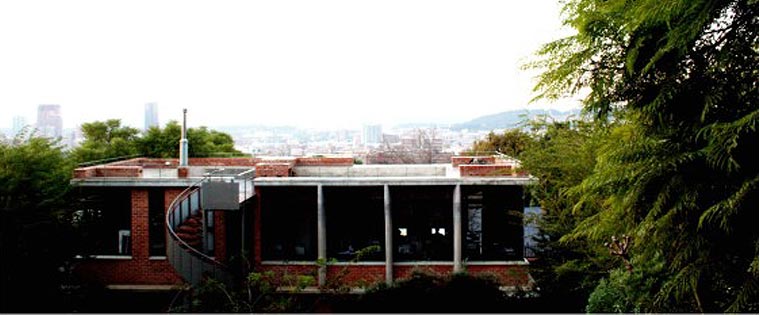

GWA is a young, dynamic, medium-sized practice, and our own brief was relatively simple: to create a flexible working environment which preferably breaks away from the prototypical architectural ‘office’. A studio ideally embodies tangible design approaches which allow a building’s inhabitants to adapt and change according to their specific needs, whether architectural, urban or management based.

GWA’s architectural studio was originally situated on the ground floor of the existing house. With sustained growth of the company, spatial requirements changed and new office space was needed. Instead of relocating the office to new premises, the existing 1970’s regionalist site (with a house placed to the back of the site and a large open area to the front) provided an opportunity for urban intervention.

The building allows for each of its users to utilize the spaces within as they see fit. Linear open plan studio spaces create a flexible and dynamic working environment, where peers are constantly interacting with and educating one another.

The design also creates an urban room within the greater city, allowing a number of designers to participate and personalise the environment to form a greater outcome, the same as when designing a city.

The new office ideally acts as a habitable dam wall that is situated on the perimeter of the site. Conceptually, this ‘dam wall’ ideally functions as a catch pit for existing and new entities. Predominantly orientated to the north, the northern façade acts as a barrier whilst the southern façade opens visually, and physically links to the new courtyard space.

The primary concern was not to obstruct the beautiful views from the ground and first floor levels of the existing house. The new office ideally shares the same approach and acts as the primary generator for its physicality and tectonic response.

Noticeably, the building’s footprint has a knuckle, and ever so slightly bends at its core. The visually uninterrupted soft bend mimics the curve of the street as one approaches the building from street level. The planters, seating spaces and patterned, paved parking on the northern street scape is reminiscent of the original boundary wall. These subtle interventions allow for articulated communal spaces on street level.

The position of the new laboratory building is along the southern edge of the site, along George Storrar Drive. The building has been divided into an estimated 8000m² for laboratories (over three floors) and an additional 1700m² for possible Conference facilities. The space between the existing buildings and the new would become a landscaped pedestrian “street”. Essentially, three simple boxes form courtyards in between another. From the street, the boxes allow momentary glimpses into the otherwise inaccessible laboratory spaces. Seemingly a box within another box, each has a double skin that offers opportunities to accommodate services.

The structural grid of the existing buildings provided cues for the structural modular of the new building, while other formal cues were taken from the modernist neighbour. Extensive research was done on the latest architectural devices for laboratories, both nationally and internationally. Amongst others, this determined the provision of peristitial space for services, while also informing the flexible 3m-modular to allow for flexibility over time.

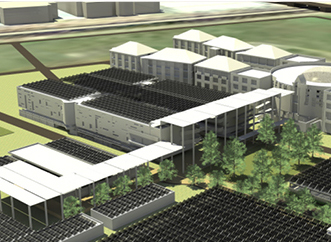

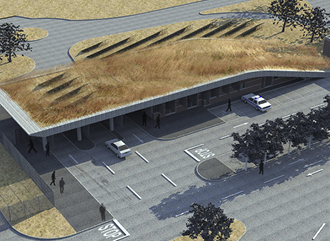

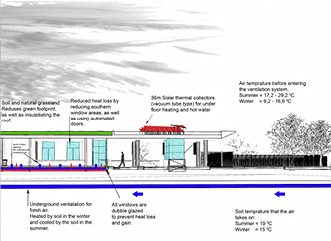

Instead of filling more urban space when building, the new Welcome Centre at the Development Bank of Southern Africa (DBSA) in Midrand, decided to keep energy efficiency, architecture and landscape in the forefront of their minds. Architects Holm Jordaan Group built the new Welcome Centre to look like a continuation of the landscape, disguising itself as Highveld savannah with its functions neatly tucked underneath and merging wall and roof into a single entity. The green design provided the building with a well insulated roof that replaced some of the Highveld vegetation. Indigenous plants and landscaping were introduced and full site rehabilitation was done after construction. Trombe walls were introduced in the northern walls to create the correct solar heat gain in winter.

All storm-water for landscaping is treated in situ with a retention dam collecting storm water, while also supporting existing bird and wildlife. Retention of storm water on site also reduces the demand on the City Council storm water system. Another noteworthy distinction of the building is that it is completely off-grid and CO2 neutral.

Earth excavation offers temperature control system opportunity

Collapsing soil conditions on site necessitated the earth to be excavated to a depth of approximately 3m and replaced with suitable material. This deep excavation offered a cost-effective opportunity to use the earth’s constant temperature as a control system: Fresh air supply is drawn into the building via underground pipes, thereby pre-heating the air in winter and pre-cooling it in summer.

Natural light permeates the small building, while artificial high-efficiency lights further reduce energy demand and heat gain. A solar water heater provides warm water for under floor warmth in winter and all year domestic hot water. According to the energy specialist of the Welcome Centre, Henning Holm from Omnibus Engineering, energy use will be a fraction of that of a conventional building of the same size. Their vital statistics for the Welcome Centre include the following:

Energy efficiency at the Welcoming Centre

Solar hot water plant:

- 34 m2 solar vacuum collector

- 1 600-litre storage tank

- 240 m2 under floor heating

Solar photovoltaic plant:

- 29.4 kW solar panels

- Producing 54 248 kWh/annum

- Battery storage = 217,7 kWh

- Equals all electricity requirements for the building

Energy efficiency:

- Demand has been reduced through efficiency from 38.4 kVA to 9.96 kVA

The client, Sasol Nitro and Dyno Nobel, a subsidiary of the petroleum company Sasol, manufactures explosives for the mining industry. The brief was to upgrade their current facilities at Ekandustria, Bronkhorstspruit in order to reflect the company’s slogan of “Reaching New Frontiers”. This included additions and alterations to the existing administration, recreation and security access control buildings. The existing built environment reflects a distinct functional aesthetic-the structures are designed so as to deflect in case of accidental explosion. This also requires a tight control and flow of personnel that deal with the manufacturing process.

A large boardroom, reception area, ablutions, offices and conference spaces were added to the existing administration buildings. These new facilities were appropriately massed so as to improve linkage to an existing over-scaled three-storey steel framed workshop. The structure and construction reflects a distinct contrast with the existing through the use of colour, form and material. In the boardroom, a low horizontal window maximizes views to the Highveld landscape, with a suspended steel structured window on the south side drawing attention to a plaque commemorating those whom have lost their lives while on duty at the factory. Adjustable steel louvers on the north elevation shade the glazed openings in the summer, while admitting winter sunlight into the new offices, optimizing user comfort.

The design objective was to create a building that does not reflect the current status quo, but rather enhance the existing buildings. The new complex encloses a colonnaded courtyard that connects the new buildings to the workshop, creating a ‘breathing space’ between the administrative and industrial functions. The entrance into the courtyard also allows access to the existing offices, mediating between the old and the new.

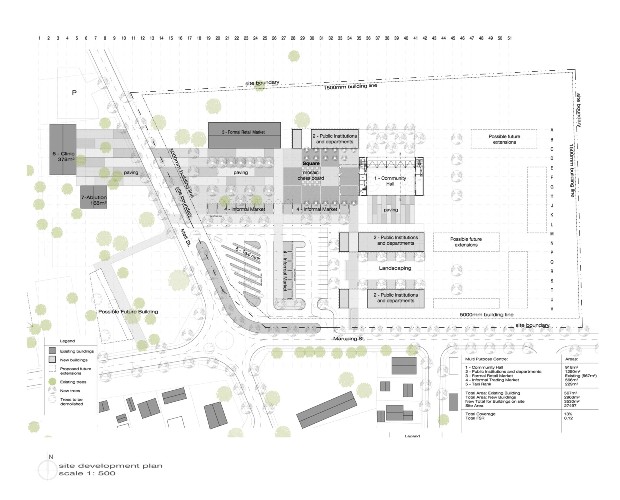

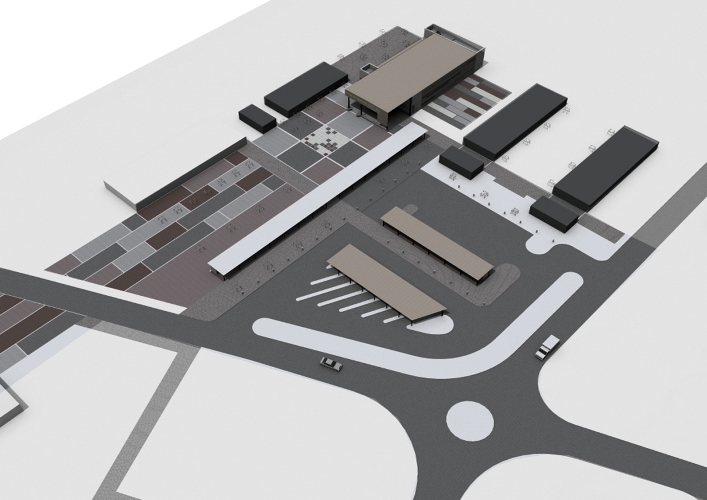

Holm Jordaan Architects and Urban Designers together with Demacon were appointed by BIGEN AFRICA to assist with urban design proposals in support of the Neighbourhood Development Partnership Grant (NDPG) submission for the Ramotshere Moiloa Municipality. The urban design concept for Ikageleng consists of three precincts, namely a multi-purpose centre, retail area and market and a sports facility node.

Four functional hard landscaped open spaces are linked via a continuous pedestrian friendly system leading from the entrance to the town along the road to the sports facilities further south. In Precinct 1 the open space is intended as an informal market square in close proximity to a proposed taxi drop-off. The Ikageleng Community Hall is the first of the projects to be implemented as part of Precinct 1.

The brief called for the design of a new transport interchange for Mitchell’s Plain Town Centre. Facilities include a taxi and bus terminals, offices for the interchange management, ablution facilities, trading facilities and pedestrian bridge across the railway line.

This is the second largest interchange in the Western Cape with over some 1000 taxis operating from here on a daily basis. An Urban Design Plan and transport study formed the basis of this project. One of the design criteria was also to deal with the harsh climate during the winter and summer, and to make the interchange between the various modes of transport as seamless, safe and comfortable as possible.

The project proposes 7th Avenue running parallel to the station to be pedestrianised. Three separate taxi terminals are proposed at the edges of the pedestrianised Town Centre, acting as magnets to draw people through the Town Centre, keeping it vibrant and alive. A large central market place allows informal traders to relocate from the congested malls in the Town Centre.

The Urban Design Framework is used to get buy-in from the various interested and affected groupings. It increases the value of the existing Town Centre by making it safer and more attractive to consumers. It enhances the value of undeveloped land and viability of future development through the strategic positioning of the various transportation facilities.

The taxi and bus shelters were designed to give protection to the commuters during inclement weather, while still providing a light and attractive environment with good ventilation to remove exhaust fumes. The same section profile was used for both terminals, based on a modular design that would enable future expansion if needed. The sides were brought down to provide protection against the elements, cladding them in GRP sheeting to allow light through during the day, and to let out at night and early mornings to light up the environment.

A family house filled with light, and courtyards and spaces for each member of the family to respond to, or for the family to enjoy as a family. The architecture responds to the site and embraces typical Highveld “farm style living”. The building has won numerous awards that include the South African Institute of Architecture Merit Award, Pretoria Institute of Architecture Merit Award.

Our brief to the architect was simple: “An unpretentious farm style house was not the only requirement; we also wanted a liveable home that compliments the entire family’s outdoor, gardening sporting and entertaining lifestyles.” (Langenhoven’s. 2007)

The designers have used the opportunity of fragments of domestic spaces as opportunity to create a home experienced with the dynamic context of views and climate as a village. Movement within and between pavilions is the organizing principle. The pavilions are the built space with a series of effective open spaces as complementary to and accentuating the total experience.

A unique theory of detail is seized to lavish the pavilions in the special no-nonsense farm detail of the region, showing how effectively this fits into the historical context. This concern integrates the elevations, typical canopies, roof’s brick courses, gutters and down pipes as the visual texture of the pavilions plus open space into a single meritorious language (Fischer. 2007).